Yes, I am stubborn enough to disagree with Francis Fukuyama 🤓

My difficulty (in writing poems—and perhaps other people’s difficulty in understanding them) is in the impossibility of my goal, for example, of using words to express a moan: ah—ah—ah. To express a sound using words, using meanings. So that the only thing left in the ears would be ah—ah—ah.

—Maria Tsvetaeva

Die herrliche Hundeschnauze

From The Lion Tracker’s Guide to Life, via Alastair Johnston:

I thought of all the people I had met who wanted a full vision for a new life and then to move from where they were straight into it. I thought of all the people who had told me that when they knew exactly what they wanted to do, then they would leave the soul-destroying thing that they were currently involved with.

Obsessed with perfection and doing it right, we want to go straight to the lion. We don’t realise the significance of the path of first tracks and how to be invested in a discovery rather than an outcome.

(Disturbing material warning)

John Lee Anderson’s piece “The Witness,” on Mazen al-Hamada is just wrenching.

During Assad’s rule, official autopsies of prisoners routinely said that “the patient died when his heart stopped,” eliding the specifics of torture. Hamada knew about these torments intimately, and during the war he travelled to Europe and the United States and gave searing testimony about Assad’s dungeons.…As Hamada spoke, he sometimes wept openly; videos of the testimony are excruciating to watch. He noted that he had witnessed others die from similar treatment, and vowed to see his torturers brought to justice, if it was the last thing he did before he died.

Mazen had been violently tortured in prison for a year and half before being released in 2013. His crimes included supporting union workers who worked for Schlumberger, protesting the torture of 15 teenage boys who were arrested for painting graffiti in Dara’a, attempting to smuggle baby formula into a “rebellious” suburb of Damascus, and of course he was also guilty of that most absurd act: simply telling the truth.

He escaped, like so many others, through Turkey and Greece, eventually gaining asylum in the Netherlands. He spent the last 5 years of his life again being tortured in prison after he chose to return to Syria in 2020. He was murdered about 10 days before the rebels took Damascus last December.

There are many, many, many like him.

I cannot think of Syria and not think of some of the images in Channel 4 News’s short 2016 video on the fifth anniversary of the war there — images which barely scratch the surface of the horror. I watch, while so many suffer.

“I am convinced,” said Jürgen Moltmann, “that God is with those who suffer violence and injustice and he is on their side.”

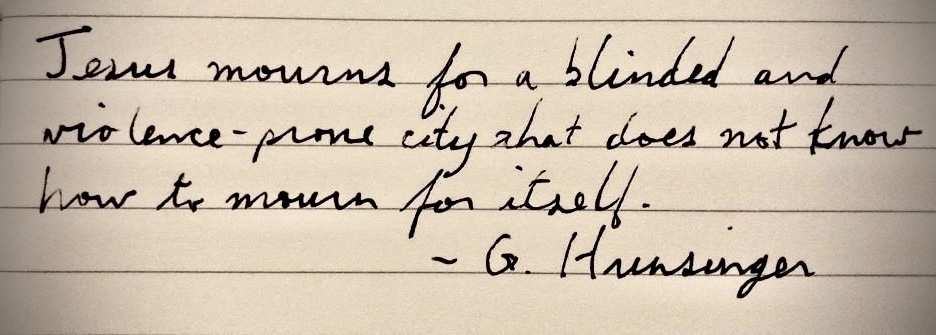

Often, the best I can muster is a silent hope that this is true, and that one day, as George Hunsinger put it, “It will be revealed to them at last that in the midst of their earthly aspirations, struggles, and persecutions, they were not alone.”

Drawing down the wealth of the world and calling it “income”:

this is a massive tragedy of the commons issue.… The seas are a classic example. Most large fish are now gone from the ocean due to what has effectively been a free for all, despite there often being such things as treaties and quotas. Fishermen typically consider themselves good stewards of the resource, but assume their competitors are plunderers — and foreign competitors are the worst. They feel compelled to increase their takes until overcapitalized fleets are competing for the last fish, and when the fishery is no longer viable, they blame it on the foreign fleets.

But every fleet is someone’s foreign fleet. That is the tragedy. And I think this fishing example can be extrapolated to our broader ecological global economic superorganism situation. “Every fleet is someone else’s fleet” is the same dynamic that we face with more and more financial claims on an underlying biophysical reality.