…

Karl Jaspers: “Such an impulse towards contemporary self-assertion culminates in a trumpeting of the present, a glorification of the passing show—as if there could be no shadow of a doubt as to what the present really is.”

It’s as if I am always hearing some strange, complicated music in the background of my life that grows intensely unpleasant when I ignore it, because it demands the attention I am giving to other things.

Wow, wow, wow! Does Tommy Dixon have my number. I think it all applies equally to reading and thinking even if no writing occurs. I will, perhaps with some irony, be returning to this.

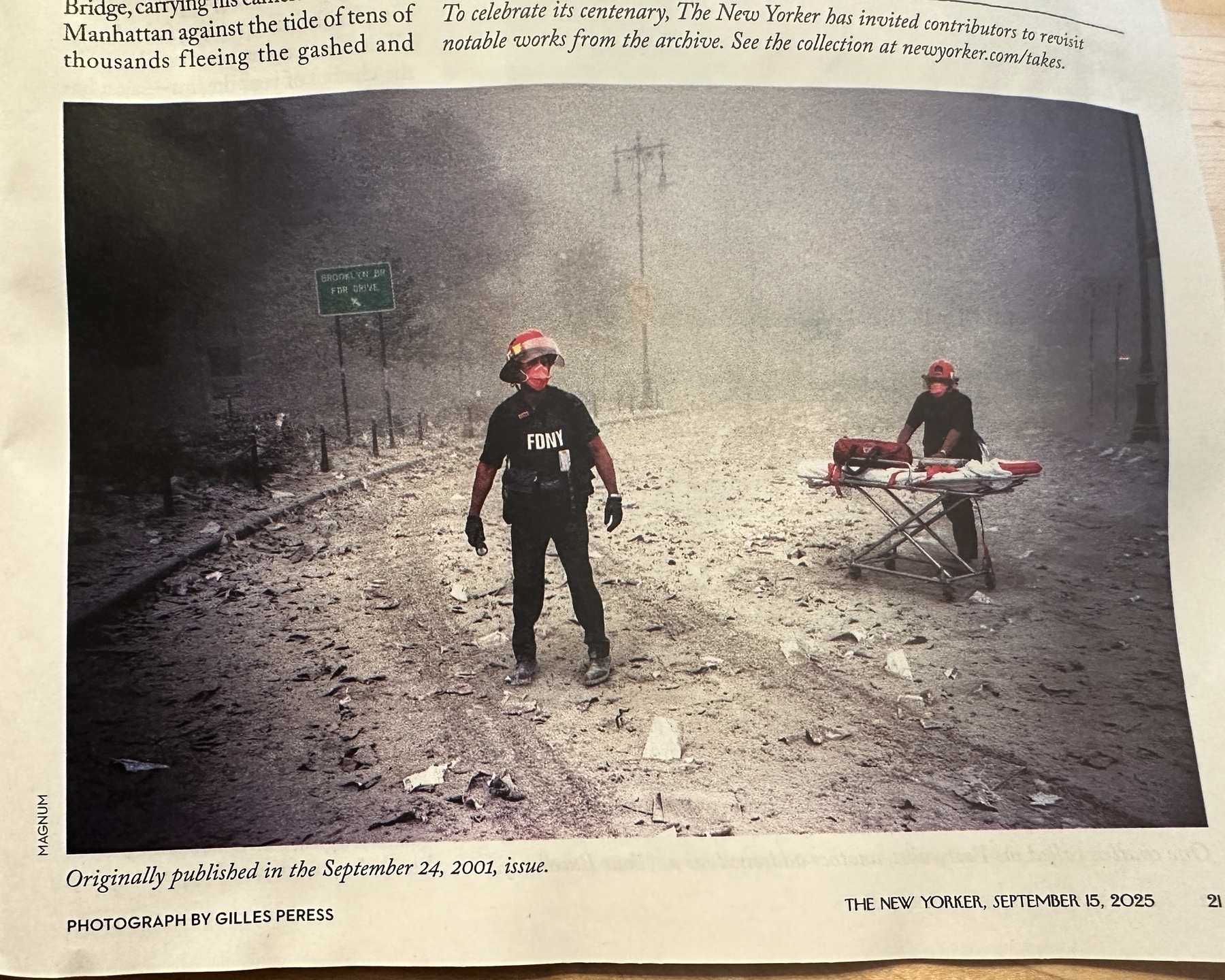

Gilles reached the World Trade Center just before the second tower collapsed. The firemen in the photograph don’t know what’s hit them. The one holding an unlit flashlight, the one with the useless gurney—they stand in their desert of ruin, frozen before the obliteration of their expectations, and ours. There it is: ashes to ashes, dust to dust, no metaphors. And yet, as we sensed in the haze of that moment and see too clearly today, it’s not a picture of an ending but, more truly, of a condition without end.

I think often of Geoff Dyer in Algiers: “As the ball hangs there, moon-white against the wall of cloud, everything in the world seems briefly up for grabs and I am seized by two contradictory feelings: there is so much beauty in the world it is incredible that we are ever miserable for a moment; there is so much shit in the world that it is incredible we are ever happy for a moment.”

I am content enough to know that both feelings are exactly right; no resolution necessary — outside of eternal hope, anyway. This is the water we swim in; rejoice with those rejoicing, mourn with those mourning. This is a loving troubledness that makes sense in the world.

But the left-right tension around me is water I simply cannot get used to swimming in.

When I look at Trumpism (and it is an ism), and all the necessary lies and hypocrisies that support it, I think How can I not side with my brothers on the left? And when I look at the celebration of murder (and that not for the first time), and all the vitriolic arrogance disguised there in colorful love, I think How can I not side with my sisters on the right?

How has everyone found it so goddamn easy to pick a side?

Where is our troubled love?

People imagine that to escape from violence it is sufficient to give up any kind of violent initiative, but since no one in fact thinks of himself as taking this initiative… this act of renunciation is no more than a sham, and cannot bring about any kind of change at all. Violence is always perceived as being a legitimate reprisal or even self-defence. So what must be given up is the right to reprisals and even the right to what passes, in a number of cases, for legitimate defence. Since the violence is mimetic, and no one ever feels responsible for triggering it initially, only by an unconditional renunciation can we arrive at the desired result…

Re-upping here:

And far from being the pious injunction of a utopian dreamer, this command [to love your enemies] is an absolute necessity for the survival of our civilization. Yes, love is the key to the solution of the problems of our world, love even for enemies.

Every single person in the country should read that sermon from MLK right fucking now. I’ve talked to six random people, in real life, face to face, about Charlie Kirk in the last hour, every one of them elated to hear the news.

God help us.

Finished reading: In Search of the Human Face by Luigi Giussani 📚

Splendid. I haven’t read a devotional-type book like this in quite a while. And never one so thoroughly quotable.

This [unbearableness due to the clamor of our weakness] is a great occasion for love, a great occasion for a loving affirmation.

The truth about our humanity cannot be reduced to the observation of its misery but to the wondrous and exalting announcement that this misery is loved. This loving, strong, and faithful presence, more than the fickle and vulnerable fragility that is the substance of humanity when left to itself, is our true richness.

Hopefully I’ll follow up with a few more, and perhaps a larger sample of quotes.