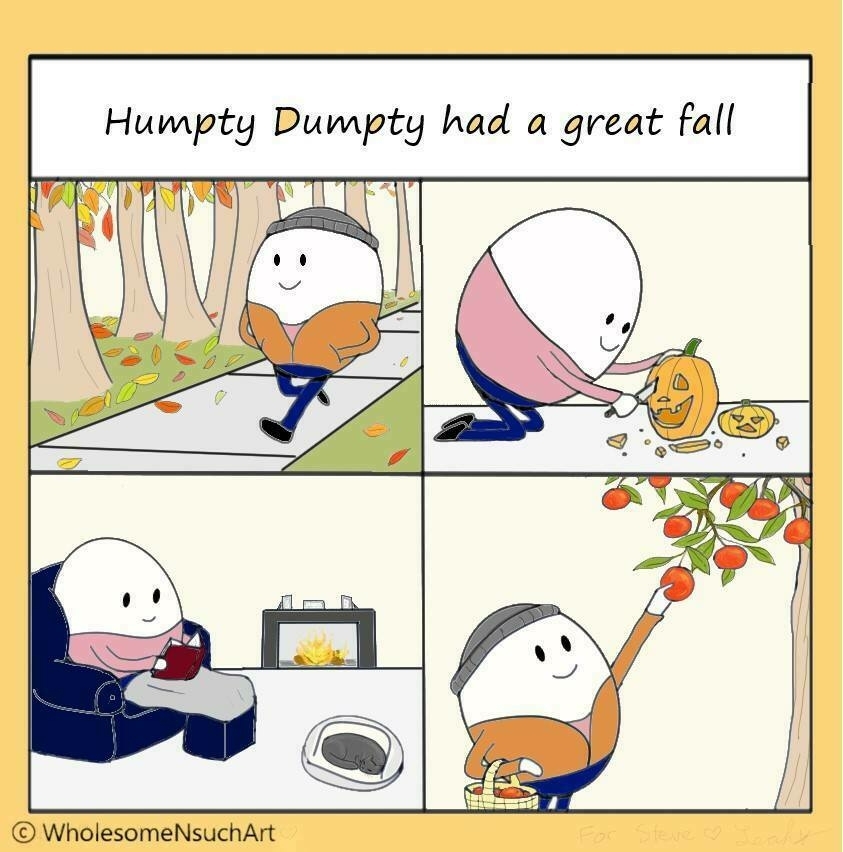

Dodge Point Ding Dong

“Look well to your sweeping and garnishing; and be sure it is only the banished spirit, or some of the seven wickeder ones at his back, who will still whisper to you that it is all black.”

—John Ruskin

Am I morally obligated to buy this??

Kingsnorth:

Wherever we come from, wherever we are, we are almost all uprooted now.… Even if you are living where your forefathers have lived for generations, you can bet that the smartphone you gave your child will unmoor them more effectively than any bulldozer could.

And, er, regardless of your age, you can bet the smartphone you are holding (or still typing this on right now)…🫵😵💫

Two things I read this morning:

Karl Jaspers in 1930:

The old antitheses—the contrasted outlooks known respectively as individualism and socialism, liberal and conservative, revolutionary and reactionary, progressive and reversionary, materialistic and idealistic—are no longer valid, although they are still universally flaunted as banners or used as invectives.

Paul Kingsnorth in 2025 (paraphrasing):

If I’m right, then the “culture war” has been little more than two bald men fighting over a comb.