[W]e are continually consenting to live in a smaller metaphysical universe, via a smaller stream of memory and sense. Why? Because it is easier, the alternative seems scary, and we’ve forgotten the difference. At times the phone has the imagined glamor of a cigarette we pick up to avoid the awkwardness of other people, and also, we not so secretly despair of recovering, thinking perhaps that alas, our brains are gone forever. To put this another way, I think we have a cow problem.

Vive la résistance ironique et paresseuse!

Prayer as dependence and duty and responsible freedom on a demanding human journey…

It’s therapeutic [splitting logs]. And it’s not a very complex job. Routine, really, but not boring. So many things that happen in our everyday lives bother us and cloud our day. Often, if I’ve been to a meeting and gotten worked up about something or other, I might go around thinking of all the things I should have said. But then, when I’m standing by the chopping block, I don’t think about any of it anymore. My mind is never so pleasantly empty as it is when I’m chopping wood.

—Arne Fjeld, a “small farmer”

in Nordskogbygda, Norway

Harvest moon peaking in and out of the clouds last night. We attempted a picnic dinner to enjoy it, to some success. I’m really not sad that pictures didn’t do justice to what what we could see; that’s as it should be.

Currently Reading: Norwegian Wood: Chopping, Stacking, and Drying Wood the Scandinavian Way by Lars Mytting 📚

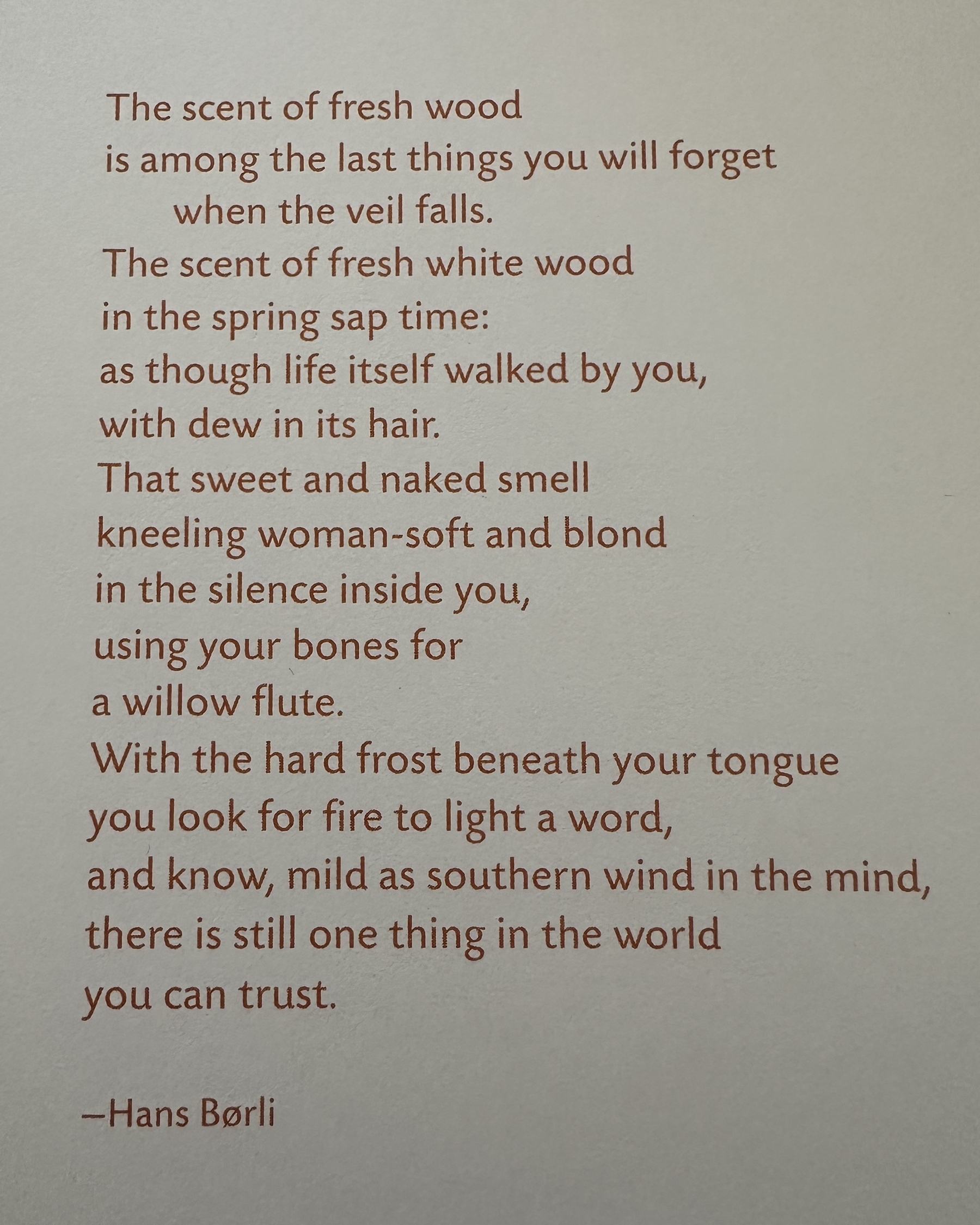

Some books you pick up, open, and buy within the span of less than 60 seconds. This is one of those. Fun to flip through, yes, but thoroughly readable, as informative as inspiring — even for a Maine-born Ben-Logger (that there’s Hebrew, fyi… I think) like myself. And Mytting picked a whopper of a poem for his epigraph: