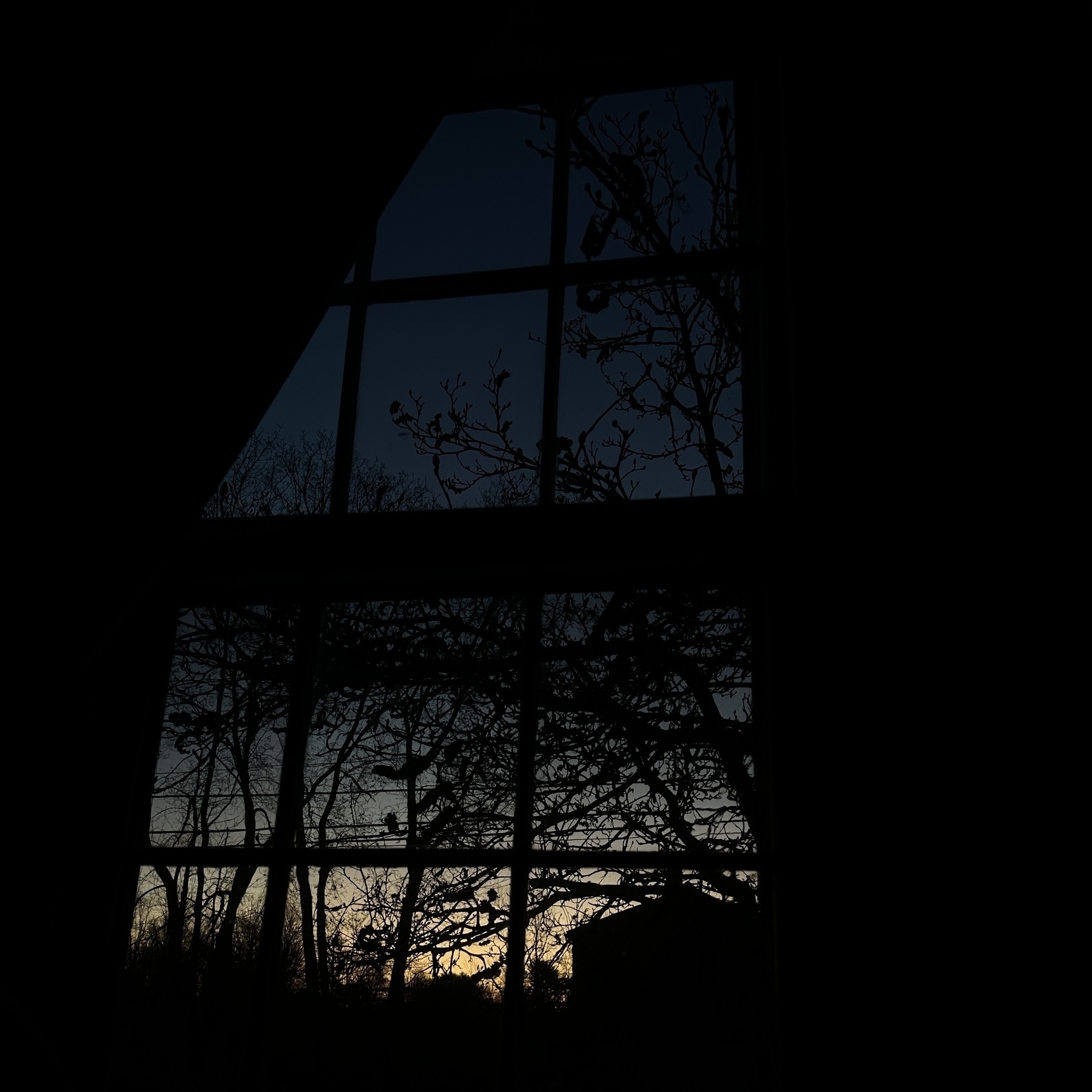

And where are the windows? Where does the light come in?

Bernie, old friend, forgive me, but I haven’t got the answer to that one. I’m not even sure if there are any windows in this particular house. Maybe the light is just going to have to come in as best it can, through whatever chinks and cracks have been left in the builder’s faulty craftsmanship, and if that’s the case you can be sure that nobody feels worse about it than I do. God knows, Bernie; God knows there certainly ought to be a window around here somewhere, for all of us.