David Whyte, on Goethe’s poem “Holy Longings” (which you should click-n-read):

So Goethe is looking at the way that we often feel like troubled guests, that we’re somehow slightly out of sync, not completely present, somehow have missed part of the information.

I always think it’s quite fascinating that we are one of the few corners of creation that’s allowed to feel as if we don’t belong. A stone is a stone; a hawk is a hawk; an armadillo is an armadillo — in its armadillo-ness. And each of the creatures in the world, and the inanimate objects of the world, or a tree, or a bush, just gets to be itself, with no argument. Whereas human beings are one of the few creatures of the world that can actually seem to be there while a good part of their identity — their imaginations, their senses of vitality and presence — can be absent completely.

Some sort of anxious not-at-home-ness is a negative potential that has probably followed human beings for our entire history. But I doubt if humans have ever more willingly made themselves — and, more importantly, their offspring — feel less at-home than we do now.

I was flipping through Nicholas Carr’s 2014 book The Glass Cage yesterday and stopped on this highlighted quote (emphasis added):

“A map is not the territory it represents,” the Polish philosopher Alfred Korzybski famously remarked, and a virtual rendering is not the territory it represents either. When we enter the glass cage, we’re required to shed much of our body. That doesn’t free us, it emaciates us.

The world in turn is made less meaningful. As we adapt to our streamlined environment, we render ourselves incapable of perceiving what the world offers its most ardent inhabitants.… The result is existential impoverishment, as nature and culture withdraw their invitations to act and to perceive.

To my memory, Carr never explicitly defines the “glass cage,” but describes it by way of a simile. A glass cage is like what pilots in the 70s and 80s started calling the “glass cockpit,” as the analog gauges in the newer flight decks were replaced with “glowing glass screens” displaying data from a computer, and the mechanical controls, with their cables and their pulleys and their tactile feedback, were replaced with “fly-by-wire” systems. This and the increased ubiquity of “autoflight systems” led to the 2013 FAA Safety Alert for Operators, with which Carr begins his book.

It may sound a little silly, but the FAA really did feel the need to write a letter saying that people who fly planes need to spend more time actually flying planes. The concern was that pilots were experiencing “skill fade” and that in situations where they were forced to manually, you know, fly the planes, they would be overwhelmed by the task of actually, you know, flying the planes.

It’s an analogy perfectly fitting for the age no less than for Carr’s entire career.

Living too much of your life through a screen — and “too much” is not much — makes even the front door of your house an increasingly overwhelming object, and the other side of that door an increasingly unwelcoming place — not because the world outside has changed, but because we have changed. As Hannah Arendt put it (in 1977!), we’ve created a radical world-alienating situation “where man, wherever he goes, encounters only himself.”

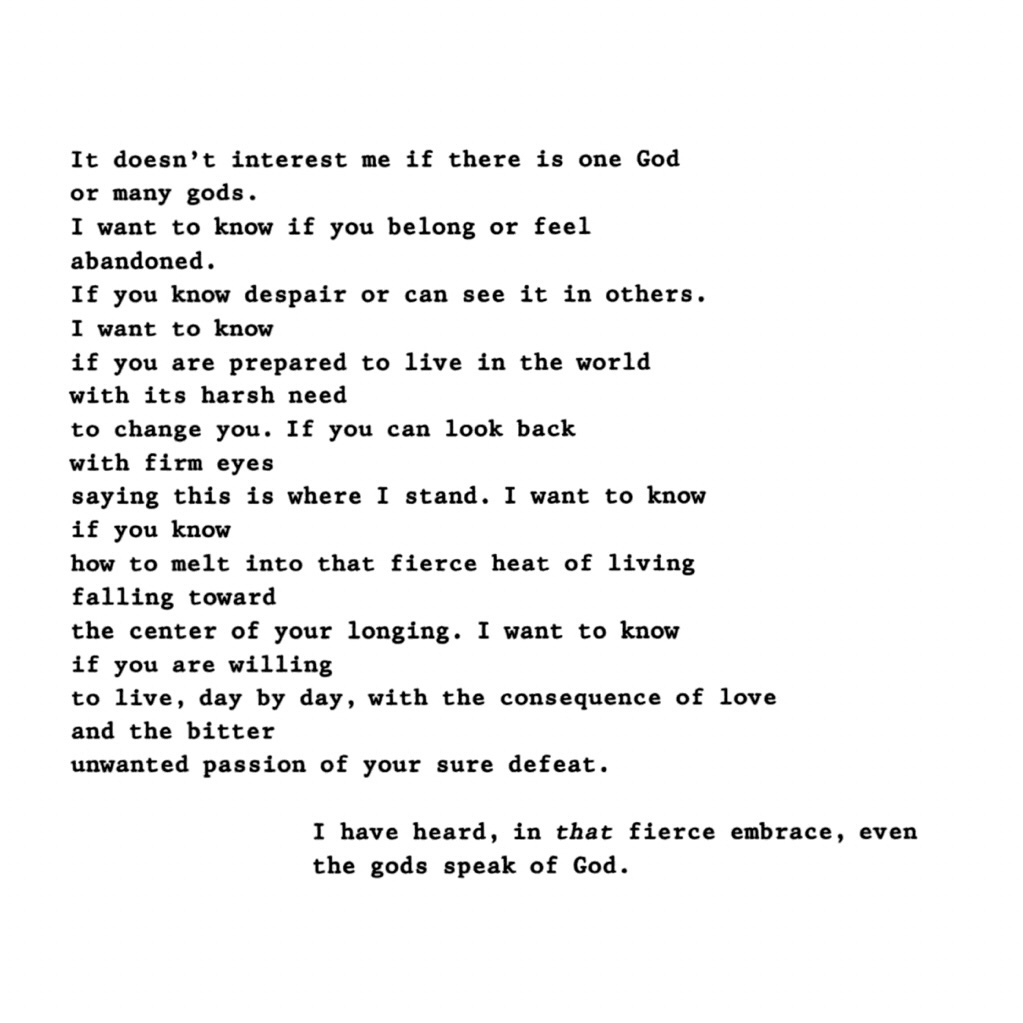

All this makes David Whyte’s poem “Self Portrait” all the more pressing and heartening.