Currently returning with the cleft surgery team from Juba, after previously spending a few weeks in Lviv. As the French say, I am le tired.

Because I’m looking for a good word on restoration, as well as for the dirty, overlooked things around the world that strain and somehow work every day; and because last week I reread Alan Jacob’s piece in Comment Magazine on “filth therapy” and “the recognition of what is of worth in that which is scorned by the unseeing”; and because now I know (unsurprisingly) how central that piece is to his thought and writing — I put up an album of photos from the cleft surgery trip with this quote in mind:

“But then what praise is appropriate for those who have taken the filth of the world and given it souls…?”

I tried to think of a good paraphrase that was more fitting to an old, rundown hospital in South Sudan, but I think the idea is fitting enough just the way it is. I will only add a line from a previous year’s journal: Sometimes our work is to make more clear and explicit what is already there, if you have eyes to see.

I’m often torn between the idea of restoring as a means of making visible what is hidden, and restoring as a means of enabling a thing to be what it was not. I’m also happy to leave this unresolved.

What goes on across the globe in hospitals like this one is not as eloquent as, say, the image and feeling of Elizabeth Bishop’s “Filling Station,” but it can be every bit as grimy and every bit as redemption-bearing. And it is capable, therefore, as Christian Wiman said of the last line in Bishop’s poem, of an immense theological statement.

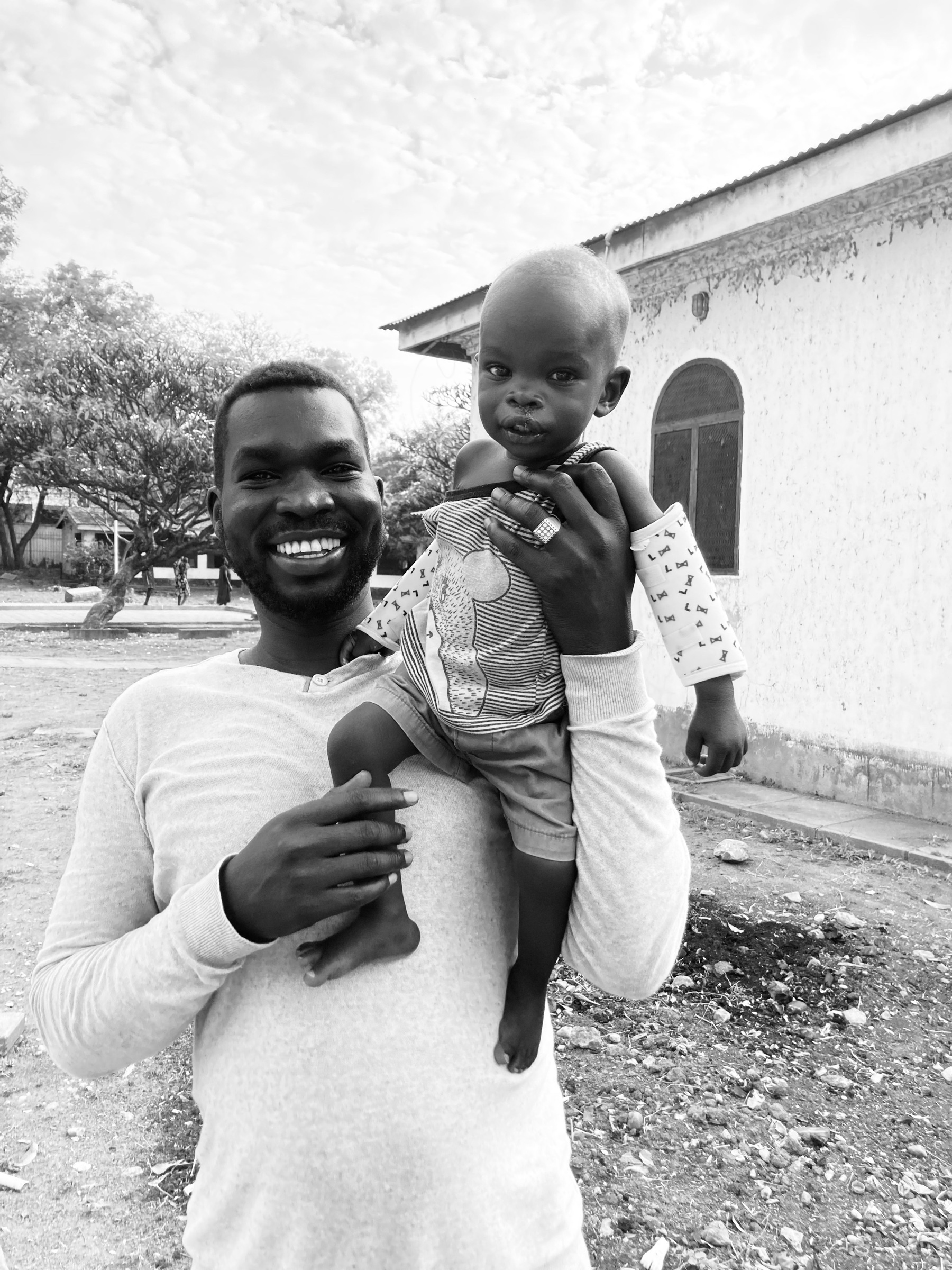

Almost everything in these pictures has contributed in some way to the work that produces — or reveals — smiles and faces like these: