Eight years ago today, I was asked to give a speech on the topic of truth at the University of Maine. I had just returned from a field hospital in Iraq after the liberation of Mosul and I had one clear thing to say. If I was given that task again today, I think I would say the exact same thing.

Life alone, life given, not exacted from others, can save a [person’s] life.

—André Trocmé

Jack: 0

Skunks: 2

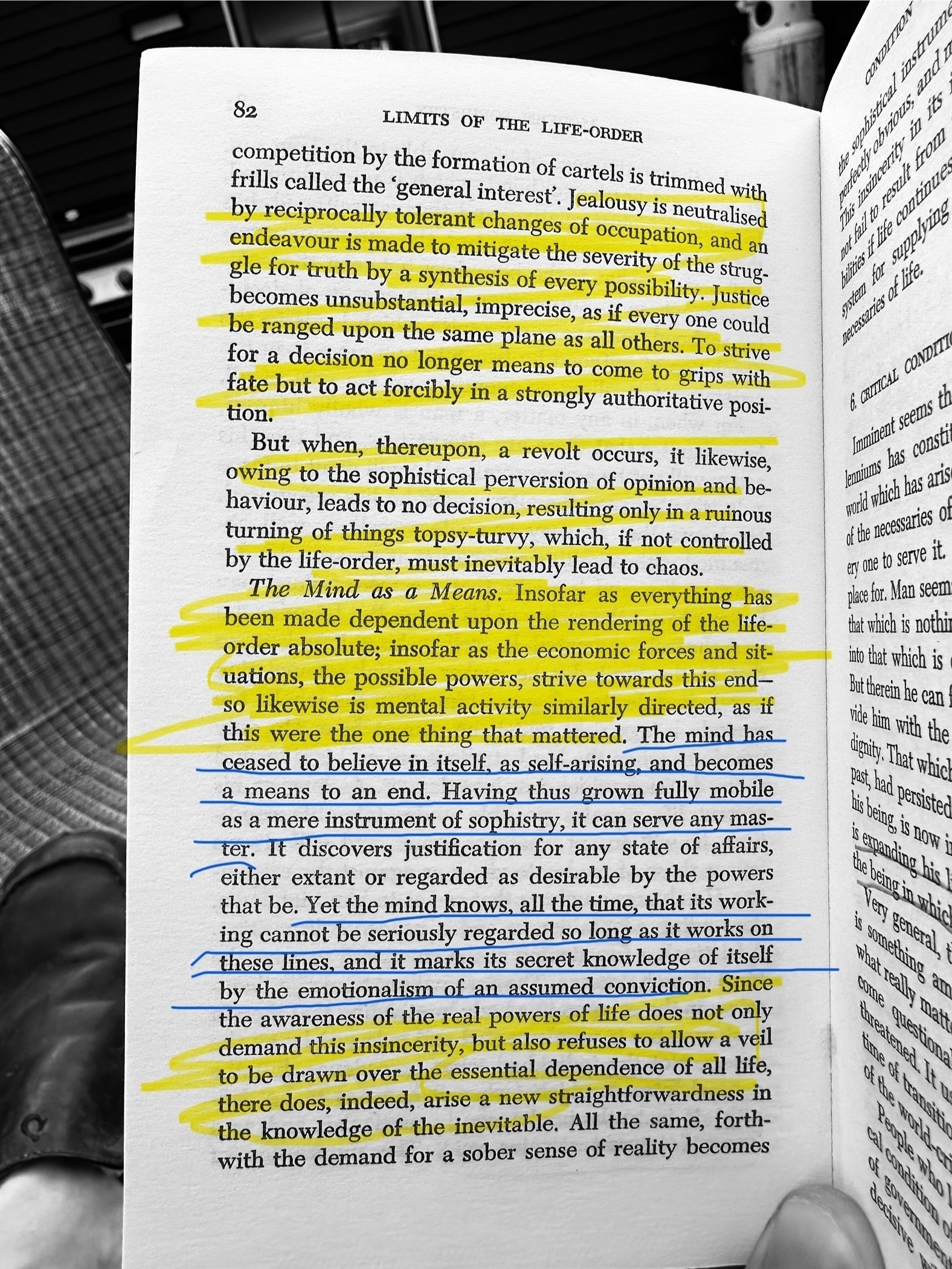

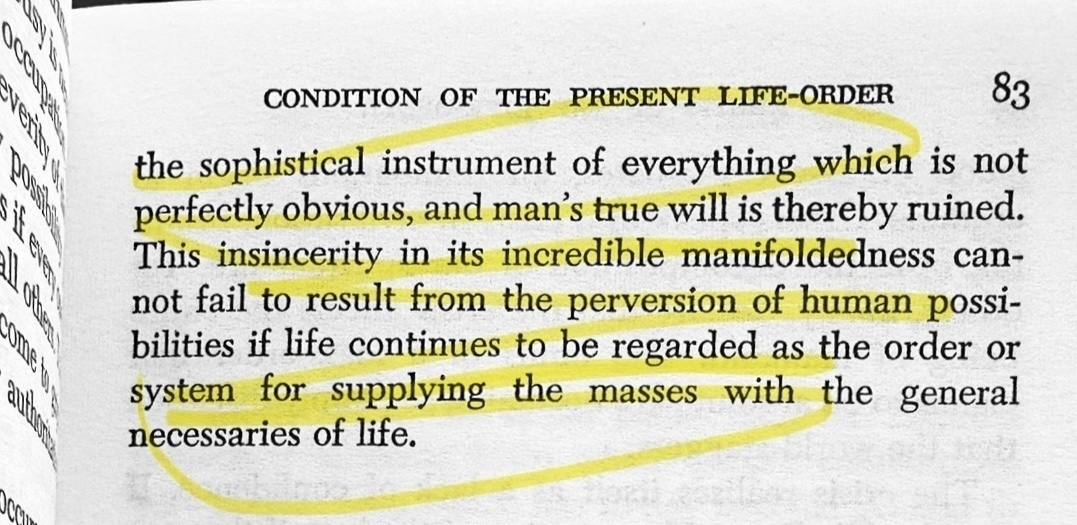

I am midway through Karl Jasper‘s Man in the Modern Age and I’ve been perpetually blown away by the relevance today of literally everything that one man said in 1930. Everything. Every sentence. No exceptions. The fact the this is a library copy and I can’t use my own pen is killing me.

The Wisdom of Not Knowing — an excellent, lovely conversation from Futurology

I … gaze through shade

Folded into shade of slender

Laurel trunks and leaves filled with sun.

The wren broods in her moss domed nest.

A newt struggles with a white moth Drowning in the pool. The hawks scream,

Playing together on the ceiling

Of heaven. The long hours go by.

I think of those who have loved me,

Of all the mountains I have climbed,

Of all the seas I have swum in.

The evil of the world sinks.

My own sin and trouble fall away

Like Christian’s bundle, and I watch

My forty summers fall like falling

Leaves and falling water held

Eternally in summer air.

— Kenneth Rexroth