Valuing seeks to dominate the material world. The entire stuff of being becomes a mere resource to be manipulated and shaped into what we value. … No wonder, then, that valuing feels bold and arrogant in contrast to the other attitudes we have examined; a world we only value is a world entirely subject to our evaluation and control.

Respect, by contrast, responds. It eschews control. It steps back before the type of thing cared about, and thus necessarily before every individual example of that type. A limit is given to us and to our schemes of domination. We can no longer destroy and rebuild as we wish; we must accept and accommodate being, even the being of individuals. If I respect human life, if I think it inviolable, then rather than making and manipulating it, I acknowledge and defer to it; I let it be. True, I may sometimes (but not necessarily or always) have a kind of attraction to the object of respect, but even here, my feeling goes beyond the achieving and holding stance that accompanies valuing, to include an appreciative awe or delight.

– Richard Stith

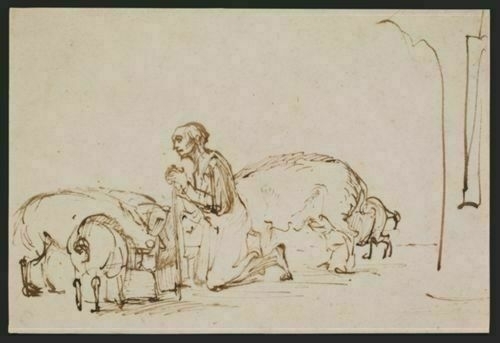

This perfectly complements the Rembrandt painting this morning

“No wonder,” says Anne Kim, “that poverty sticks around. There’s simply too much demand for it.”

Beginning in the 1980s, the U.S. government aggressively pursued the privatization of many government functions under the theory that businesses would compete to deliver these services more cheaply and effectively than a bunch of lazy bureaucrats. The result is a lucrative and politically powerful set of industries that are fueled by government anti-poverty programs and thus depend on poverty for their business model. These entities often take advantage of the very people they ostensibly serve. Today, government contractors run state Medicaid programs, give job training to welfare recipients, and distribute food stamps. At the same time, badly designed anti-poverty policies have spawned an ecosystem of businesses that don’t contract directly with the government but depend on taking a cut of the benefits that poor Americans receive. I call these industries “Poverty Inc.” If anyone is winning the War on Poverty, it’s them. […]

Perhaps the greatest damage that Poverty Inc. inflicts is through inertia. These industries don’t benefit from Americans rising out of poverty. They have a business interest in preserving the existing structure of the government programs that create their markets or provide their cushy contracts. The tax-prep industry, for instance, has spent millions over the past 20 years to block the IRS from offering a free tax-filing option to low-income taxpayers. The irony is that this kind of rent-seeking is exactly what policy makers thought they were preventing when they embraced privatization 40 years ago.

Rembrandt’s The Prodigal Son among the Swine, c.1650

With the greatest economy and delicacy, Rembrandt seems to have depicted the very moment when, from the depths of abjection, the possibility of forgiveness and so of hope dawns on the prodigal’s mind. On his knees, as if in prayer, he appears, hesitantly and tentatively, to entertain a thought like the psalmist’s: ‘there is forgiveness with thee’ (Psalm 130:4). We observe, perhaps, the very dawn of hope. But it is like the first signs seen by those who watch for the morning (v.6), no more than a glimmer—for hope, after all, need have no ground beyond the very barest intimation of possibility. We sense that the prodigal may rise from his knees.

Whether he will then be able to ‘stand’ (v.3) remains to be seen. From the depths, however, the prodigal, like the psalmist, has dreamt of forgiveness.

– Michael Banner

The allure of a window

the calling to show up

get up

and go

outside

I’m involved in a lonely war against the deployment of particular abstractions. I call it RPM theory. I believe “Religion,” “Politics,” and “the Media” are perhaps the three most catastrophically unexamined abstractions in the English language.

There is no there there.

There’s people. But there is no the religion or the politics or the media. Just people making decisions.

Most of these people can be addressed as people. It can take time and effort and fancy footwork. But addressing people as persons can be done.

It works. Maybe it’s the only thing that works.

Boys day out in Brunswick today and Will and I had two goals: acquisition of plumbing hardware ☑️ and wading through MLK Jr’s sermon “Loving Your Enemies,” delivered at the Detroit Council of Churches’ noon Lenten services. ☑️

No matter which side of whichever aisle you find yourself on, or if maybe you’re like me and don’t feel like you’re even in the same room as anyone else — many different things will be said at many different times, many of them very important, but none more perpetually relevant and requisite for us all than these “words lifted to cosmic proportions,” a command that is “an absolute necessity for the survival of our civilization”: love your enemies.

And I submit to you that the first way that one can go about loving his enemy neighbor is to develop the capacity to forgive.

The other thing that we must do in order to love the enemy neighbor is this: we must seek at all times to win his friendship and understanding rather than to defeat him or humiliate him. There may come a time when it will be possible for you to humiliate your worst enemy or even to defeat him, but in order to love the enemy you must not do it. For in the final analysis, love means understanding goodwill for all men and a refusal to defeat any individual. And so somehow love makes it possible for you to place your vision and to center your activity on the evil system and not the individual enemy who may be caught up in that system. […]

And I think this is what Jesus means when he says, “Love your enemies.” And I’m so happy he didn’t say, “Like your enemies,” because it’s kind of difficult to like some people. Like is sentimental; like is an affectionate sort of thing. And you can’t like anybody who’s bombing your home and threatening your children. It’s hard to like a senator who’s spending all of his time in Washington standing against all of the legislation that will make for better relationships and that will make for brotherhood. It’s difficult to like them. But Jesus says, “Love them,” and love is greater than like. Love is understanding, redemptive, creative goodwill for all men. And so Jesus was expressing something very creative when he said, “Love your enemies. Bless them that curse you. Pray for them that despitefully use you.” […]

And only by doing this are you able to transform the jangling discords of society into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood and understanding. […]

And this is the meaning of the cross as we move toward Easter. It is not just a meaningless drama taking place on the stage of history, but it is a telescope through which we look out into the long vista of eternity and see the love of God breaking forth into time. It is an eternal reminder to a power-drunk generation… Love is the only answer. And so this morning, as I look into your eyes, as I lift my eyes beyond you and look into the eyes of the peoples of the world, I love you. I would rather die than hate you. And I believe that my spirit can meet your spirit, and your spirit, through this process, will meet my spirit; and through this collision of spirits, the kingdom of God will finally emerge.

“Just lemme suck on your chin”

Will and I are really enjoying JD Hunter’s Democracy and Solidarity, which I read to him every morning. So far it’s been a broad, and insightful, overview of America‘s “Hybrid-Enlightenment.” There is a subject, though, that rubs me the wrong way every time it’s mentioned: religious knowledge.

Here’s Hunter:

At the same time that religion remained symbolically important to local and national civic life for the broad mass of Americans, it was, as it turned out, without a great deal of substance. It was a remarkable paradox. To take one example, Bible distribution increased 140 percent between 1949 and 1953. Moreover, eight of ten Americans believed that the Bible was not merely a great piece of literature but in fact the revealed word of God. Yet most Americans couldn’t name the first four Gospels and more than half couldn’t name one of them. Americans revered Scripture, but apparently didn’t read it.

There’s a broader point being made that I don’t dispute. And I certainly take issue with and lament disparities between religious conviction and quality, belief and practice, faith and fruit. But, as I’ve written about before, I’ve never been shown a correlation between religious knowledge and practice. In fact, my assumption is that throughout most of history most people have remained happily, if not beneficially, ignorant of the fine details that move them.

When in history has this not been the case?

I believe it was Stanley Hauerwas who said that most American Christians actually needed their bibles taken away from them. I have for years found it difficult to disagree, and I don’t think it would do an ounce of harm, neither to the truth nor to religious practice.