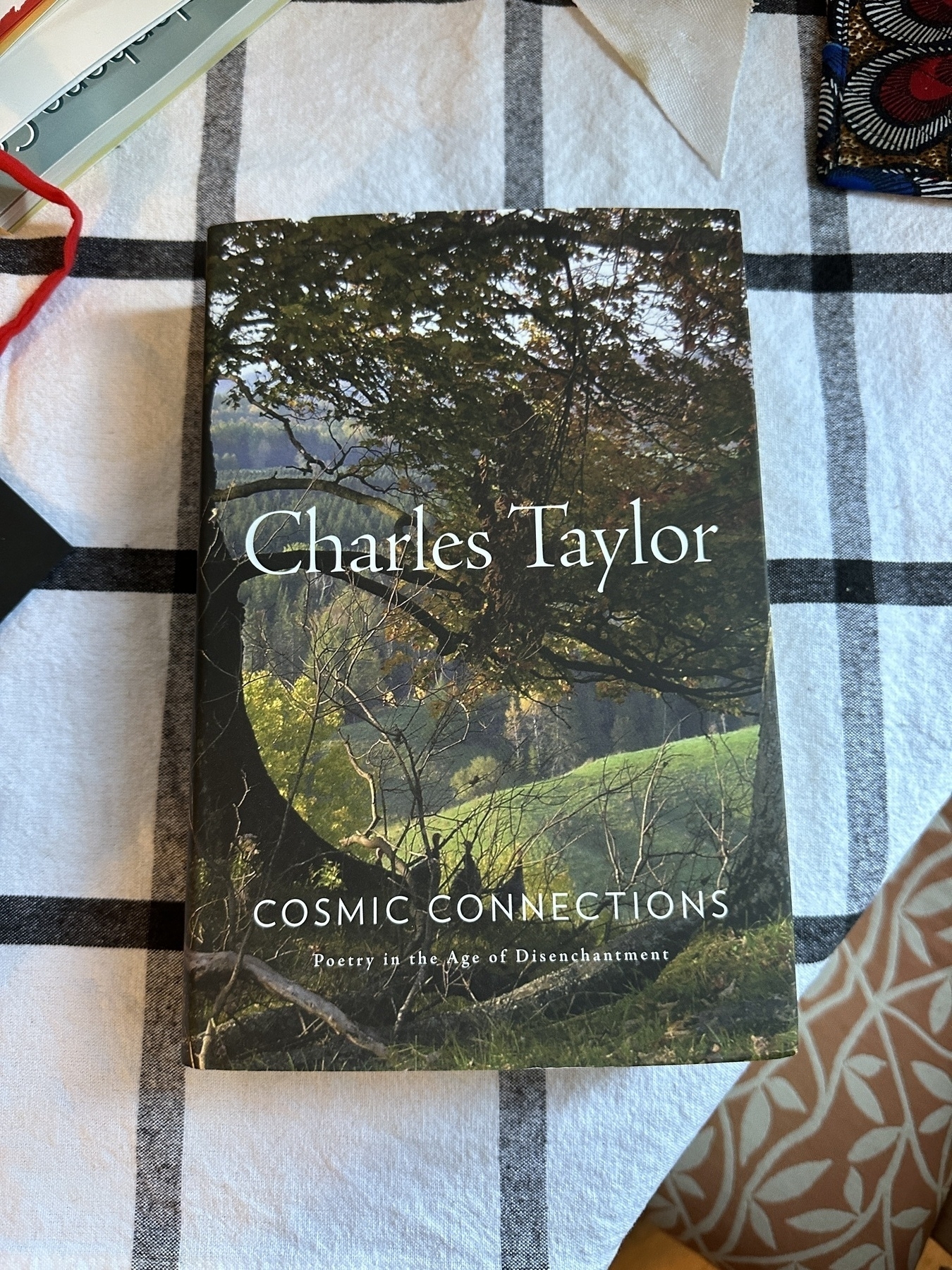

📚Happy New Book in the Mail Day! Celebrate accordingly — by putting it on the shelf behind all the other books you’ll read “very soon.”

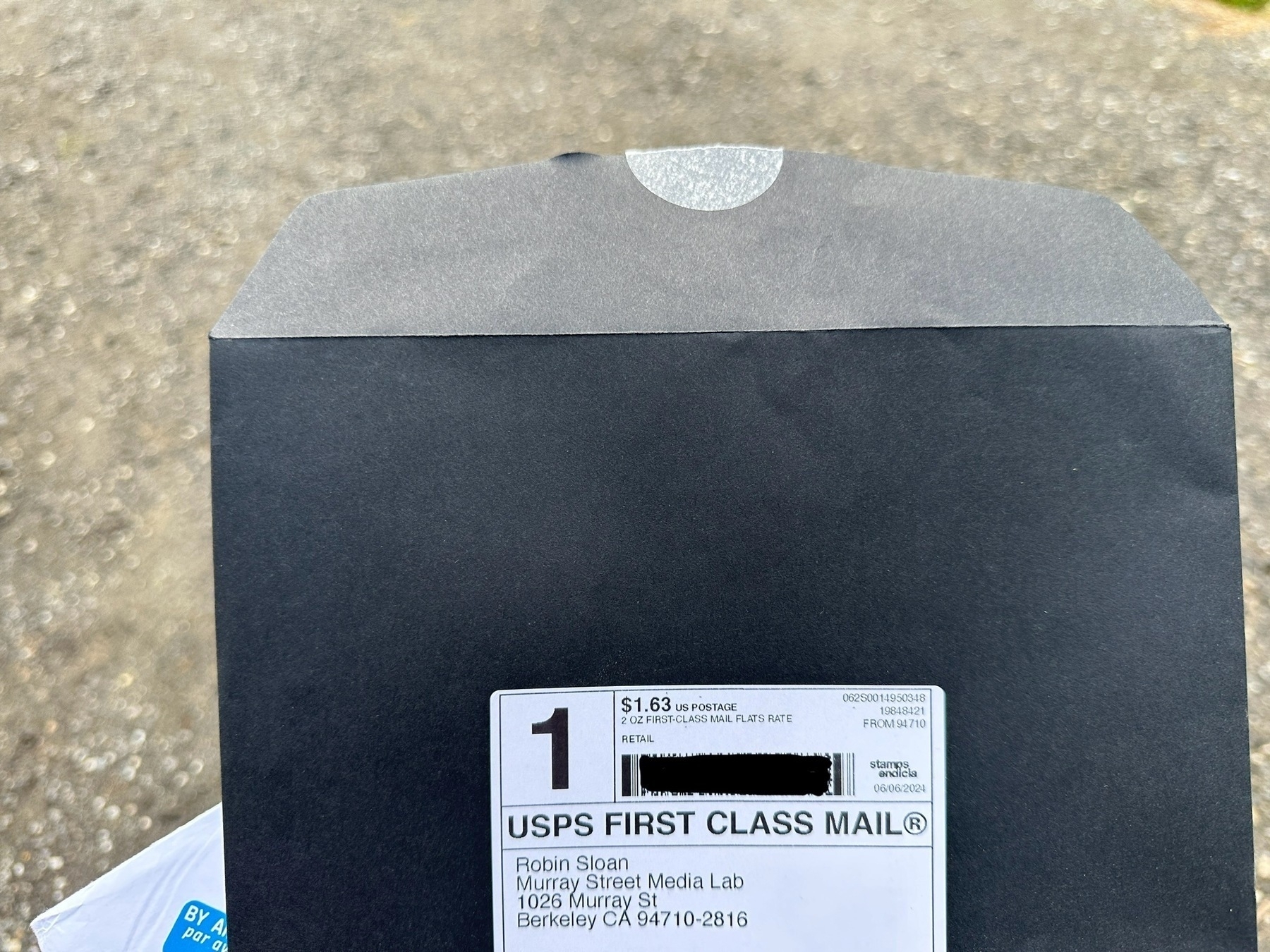

Oh boy! A letter from across the pond and something from Robin Sloan that I don’t even remember signing up for. Some days, the mail box is just full of goodies 🙂

Sanctuary of the Lord of Tula, Mexico (Photographed by Rafael Gamo)

How does one define “church architecture”? A whitewashed chapel, topped by bell and steeple? A vaulted Gothic cathedral? Further, if you wish to learn about church architecture, where would you begin? Generally, definitions are relegated to the domain of the art historian, with textbooks written to organize “church architecture” into a cleanly defined lexicon of styles and substyles.

However, I’d like to position “church architecture” as the convergence of two distinct domains: church and architecture. The domain of the church is not a fixed religious entity but rather a spiritual frontier. Second, the domain of architecture is not merely a profession but an intellectual frontier. Thus, “church architecture” should not be understood as a fixed definition but rather as an emergent territory between the ever-expanding frontiers of knowing and being.

One of my most memorable experiences of “church architecture” was a corrugated sheetmetal shack that occupied the corner of a terraced slope in Petku, Nepal.

The church had an open, arched sheetmetal foyer before the entrance. Inside, the room spanned perhaps 10 feet by 20 feet, with floral rugs covering the entire floor. At the front was a slightly raised podium, covered by a turf rug. On it, surrounded by two small benches, sat a stained lectern decorated with a cross over a white and orange Plumeria.

And that’s it. A limited opportunity for church architecture if there ever was one. Significantly, though, it didn’t feel limited by its limitations. It was quaint, clean, reverent, and attended to.

As Alain de Botton put it:

We may need to have made an indelible mark on our lives… before architecture can have any perceptible impact on us, for when we speak of being “moved” by a building, we allude to a bitter-sweet feeling of contrast between the noble qualities written into a structure and the sadder wider reality within which we know them to exist.

It was in 2015 when I visited Petku, and that little church building existed within the sadder wider reality of a devastating earthquake.

But it — the building and its attendees and attenders — existed beautifully within that wider reality.

From a 2012 interview with Jürgen Moltmann:

Were you not then [after the war] obliged to do theodicy?

No. I am convinced that God is with those who suffer violence and injustice and he is on their side. He is not the general director of the theatre, he is in the play.

In your new book, Ethics of Hope, you say that people can be awakened from a dark night of the soul and again experience an unconditional love for life. Is that what happened to you after the war?

Well, three things I still remember. One was the cherry tree blossoming in Belgium in May ‘45, which gave me an overwhelming feeling for life after the darkness and coldness of the prison camp.

And then the humanity of the Scottish workers and their families, who were amazing. They felt solidarity with us because they felt they, too, were victims of violence and injustice from their own government, in 1926 when Churchill [broke] the General Strike [and sent them back] down the mines.

And then there was the Bible I received from a chaplain. These three things convinced me to love life again.

“Something to do with dignity, something to do with luck, something to do with grace.”

“I only drive when I want to.”

For consider what has not been destroyed: music, poetry and art; the sacred texts and the secular knowledge that derives from them; the impulse to love and to learn, which will vanish only with the human species; the still-warm habit of association and institution-building, into which all our better impulses may feed. These are the counters to despair, and the source of hope in any age. Society depends on the saints and heroes who can once again place these things before us and show us their worth. This is not a task for the politician, whose proper role is not to create a society but rather to represent it. It is a task for the educator, the priest and the ordinary citizen whose public spirit is aroused on behalf of his neighbours.

As Scruton goes on to say, the “trivializing materialists and sarcastic cynics” will always make this difficult and force all too many people into hiding. But in our best moments we accept the ridicule and don’t mind sounding ridiculous, for “the best is always mocked by that which feels condemned by it.”

I always want to add a note of caution with this sentiment, since it can so easily swing over to a heedless indifference. Be helpful always, but never assume you are helping.

Lastly, regardless of the scorn, a proper human confidence doesn’t need a movement or a following or a crowd but can “take comfort in handing on knowledge to one person.”

And I think sometimes that one person will just be yourself.