Juvenile Kittiwakes putting on a late-morning show for Will

Juvenile Kittiwakes putting on a late-morning show for Will

Finished “reading”: Against the Machine by Paul Kingsnorth 📚

A man after my own heart — even where I have differed from him. I was quite moved by his Erasmus Lecture last year, but I have read and followed very little of Kingnorth, so this was a welcomed collection and update of his Substack writings. And I think — I hope — his is a voice more can listen to, can actually hear, and genuinely and generously converse with.

For now, the useful work seems to be that outlined by Joseph Campbell: to conquer death by birth. Simone Weil concluded her study of the rootless West by suggesting that the best response for we who find ourselves living in it is ‘the growing of roots’ — the name she gave to the final section of her work. Pull up the exhausted old plants if you need to – carefully, now – but if you don’t have some new seed to grow in the bare soil, if you don’t tend it and weed it with love, if you don’t fertilise it and water it and help it grow: well, then your ground will not produce anything good for you. It will choke up with a chaos of thistles and weeds.

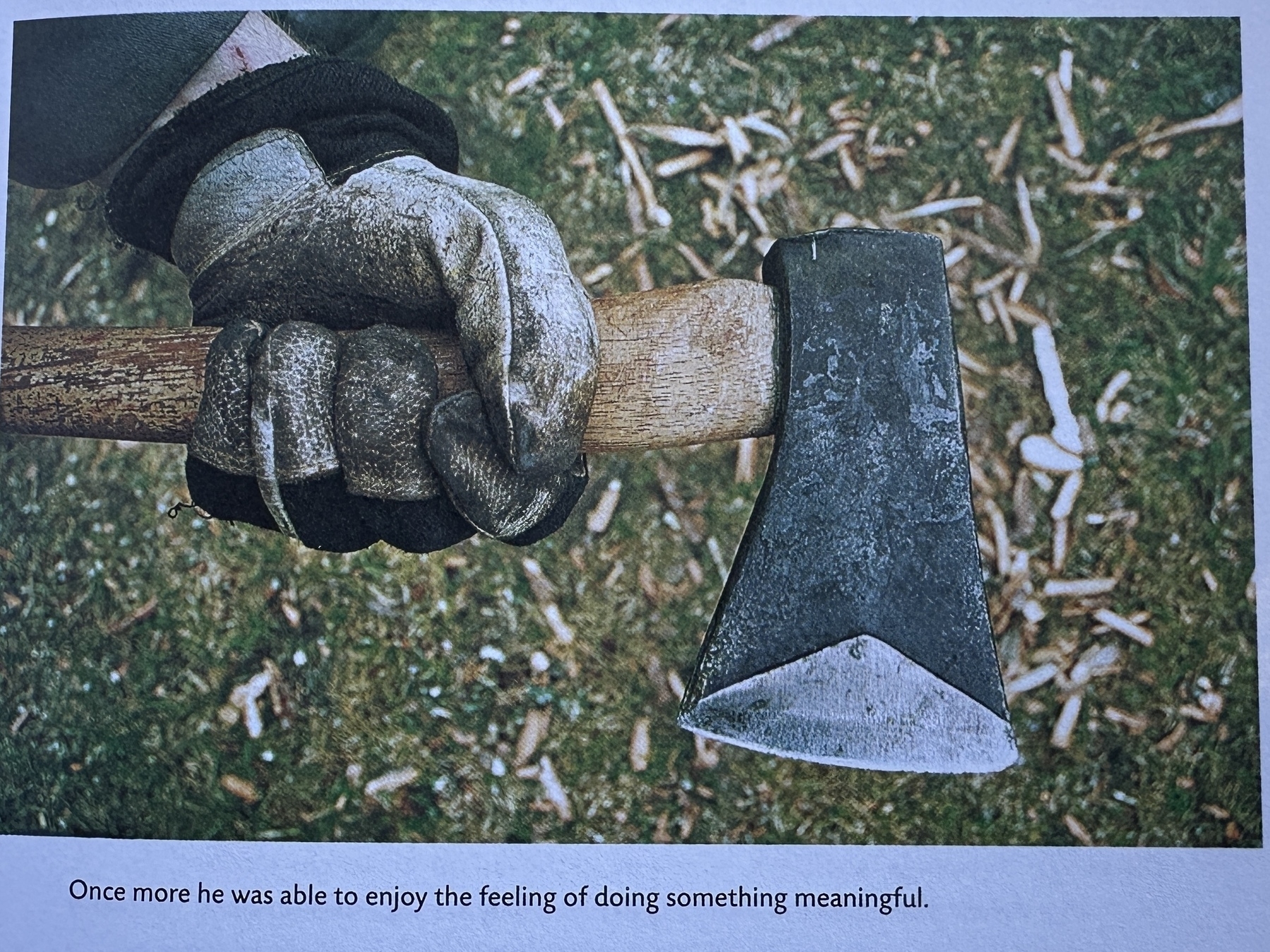

This, in practical terms is, the slow, necessary, sometimes boring work to which I suspect people in our place and time are being called: to build new things, out on the margins. Not to exhaust our souls engaging in a daily war for or against a “West” that is already gone, but to prepare the seedbed for what might, one day long after us, become the basis of a new culture. To go looking for truth. To light particular little fires – fires fuelled by the eternal things, the great and unchanging truths – and tend their sparks as best we can. To prepare the ground with love for a resurrection of the small, the real and the true.

Consider me simpatico.

“He takes what he has created and while leaving it still entirely created, raises it up…”

Mr. Jeffrey Foucault “in quartet form” plus one, Whitney Roy of the Old Hat Stringband who opened in duo with her husband Steve last night in Portland, ME. Some music brings you right down to earth in the best way. This was that.

Finished reading: Man in the Modern Age by Karl Jaspers 📚

The significance of entering into the world constitutes the value of philosophy. True philosophy is not an instrument, and still less is it a talisman; but it is awareness in the process of realisation. Philosophy is the thought with which or as which I am active as my own self. It is not to be regarded as the objective validity of any sort of knowledge, but as the consciousness of being in the world.

I would love to do a better write-up here, but time ain’t on my side. Instead, some notes I took along the way:

The present moment seems to be one which makes extensive claims, makes claims it is almost impossible to satisfy. Deprived of his world by the crisis, man has to reconstruct it from its beginnings with the materials and presuppositions at his disposal. There opens to him the supreme possibility of freedom, which he has to grasp even in face of impossibility, with the alternative of sinking into nullity. If he does not pursue the path of self-existence, there is nothing left for him but the self-willed enjoyment of life amid the coercions of the apparatus against which he no longer strives. He must either on his own initiative independently gain possession of the mechanism of his life, or else, himself degraded to become a machine, surrender to the apparatus.