The Bath Swing Band, playing the 1939 song “Undecided”

This makes me think that Doorley and Carter’s Assembling Tomorrow would make a great companion book to Haidt’s Anxious Generation.

Happy Birthday month (we think)!

What if climate change is a hoax? Well, even granting the hypothetical, it’s entirely possible that the list of things we should be doing wouldn’t change much.

Meanwhile…

~Wendell Berry~

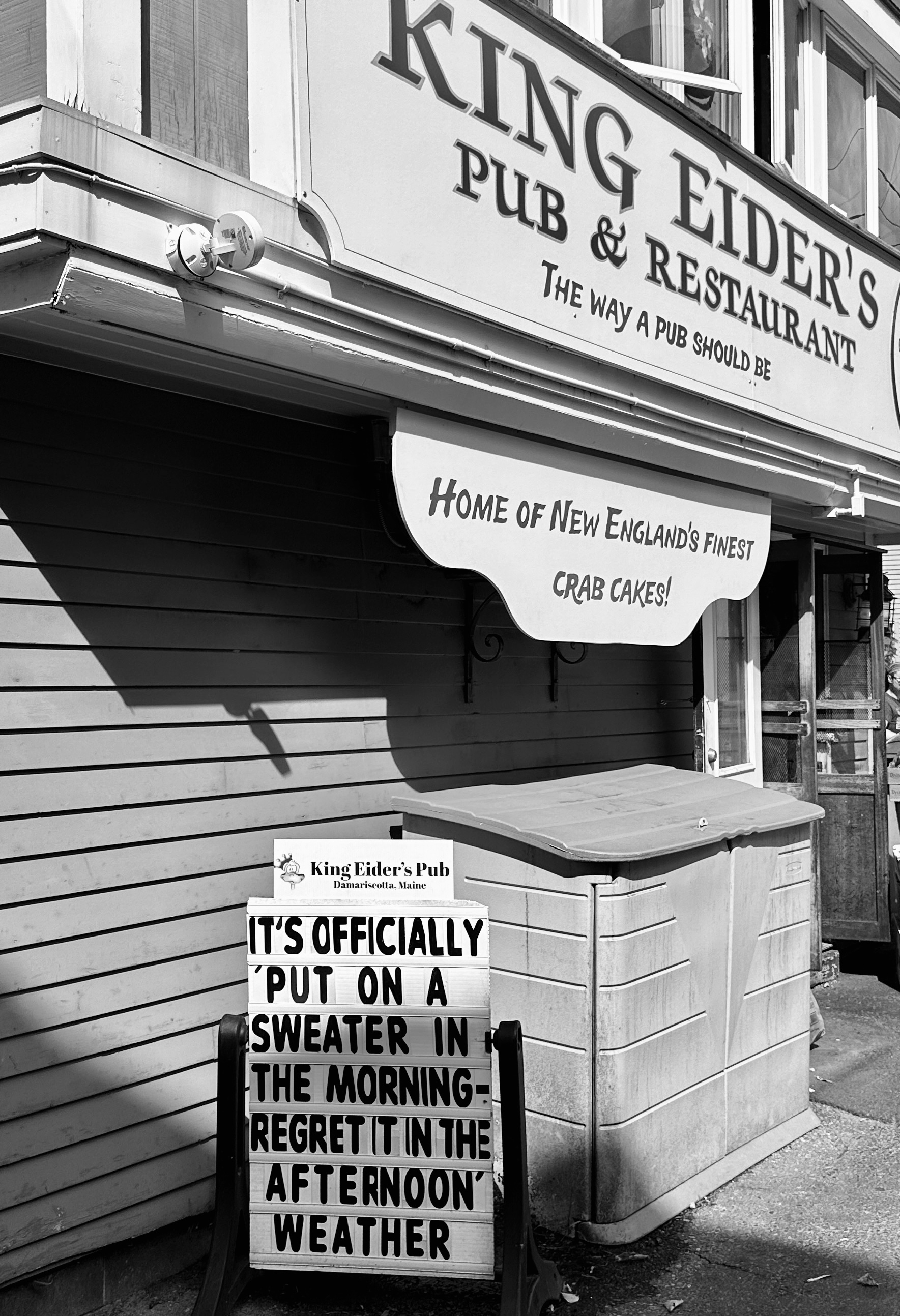

Yup.

I love Chesterton’s line, “For we have grown old and our father is younger than we are.” But I didn’t know that Augustine said it first.

This really makes me want my own VHS shrine in our house

A message and a link from my friend Luke: “A four hour and forty minute treatise by the three greatest philosophers to walk the planet.”

Hear! Hear!

The magic of the revolving door.

Not settling for moral outrage but instead holding out for moral compass.

It’s not about reaching people but asking yourself “Can you be reached? Can you receive people?”

“Sometimes it is necessary to reteach a thing its loveliness.” (From Galway Kinnell’s arresting poem)

And there’s so much more from this conversation with Greg Boyle from No Small Endeavor, which was the best thing I have listened to in as long as I can remember.

And a thousand total perfect strangers stand and they won’t stop clapping. And all Mario can do is hold his face in his hands, overwhelmed that this room full of strangers had returned him to himself. And they were reached by him, which returned them to themselves. Which is the way it’s supposed to work.