Drive-by sunset, where the Sheepscot branches into Back River

Drive-by sunset, where the Sheepscot branches into Back River

Nick Catoggio:

We deserve what we get now. And I do mean “we.” I deserve it too.…

I regret, and will always regret, that I didn’t recognize until very late what the conservative movement was becoming. I plead stupidity, not malice: Not until Trumpmania exploded in 2015 did it dawn on me that adherents of populist conservatism were happy to jettison the conservatism so long as the populist demagoguery got turned up to 10.

Whatever minuscule contribution I may have made toward us arriving at this moment, I’m sorry for it. All I can do to atone is make another minuscule contribution toward trying to lead us away and accept that, whatever Trump has planned, I’m part of the “we” that has it coming.

Wendell Berry:

[That the ends justify the means] is a vicious illusion. For the discipline of ends is no discipline at all. The end is preserved in the means; a desirable end may perish forever in the wrong means. Hope lives in the means, not the end.

I’m fine with hyperlinks — I use them, I find it useful when others use them. (I am an addicted pursuer of footnotes.) But not when the hyperlink is a stand-in for context! It’s infuriating to have no idea what’s being referred to unless I click the link. And the newsletter writers from The Dispatch are the worst offenders. If I completely refused to assume any references, it would take me a week to read half of one email from Nick Catoggio.

End of rant.

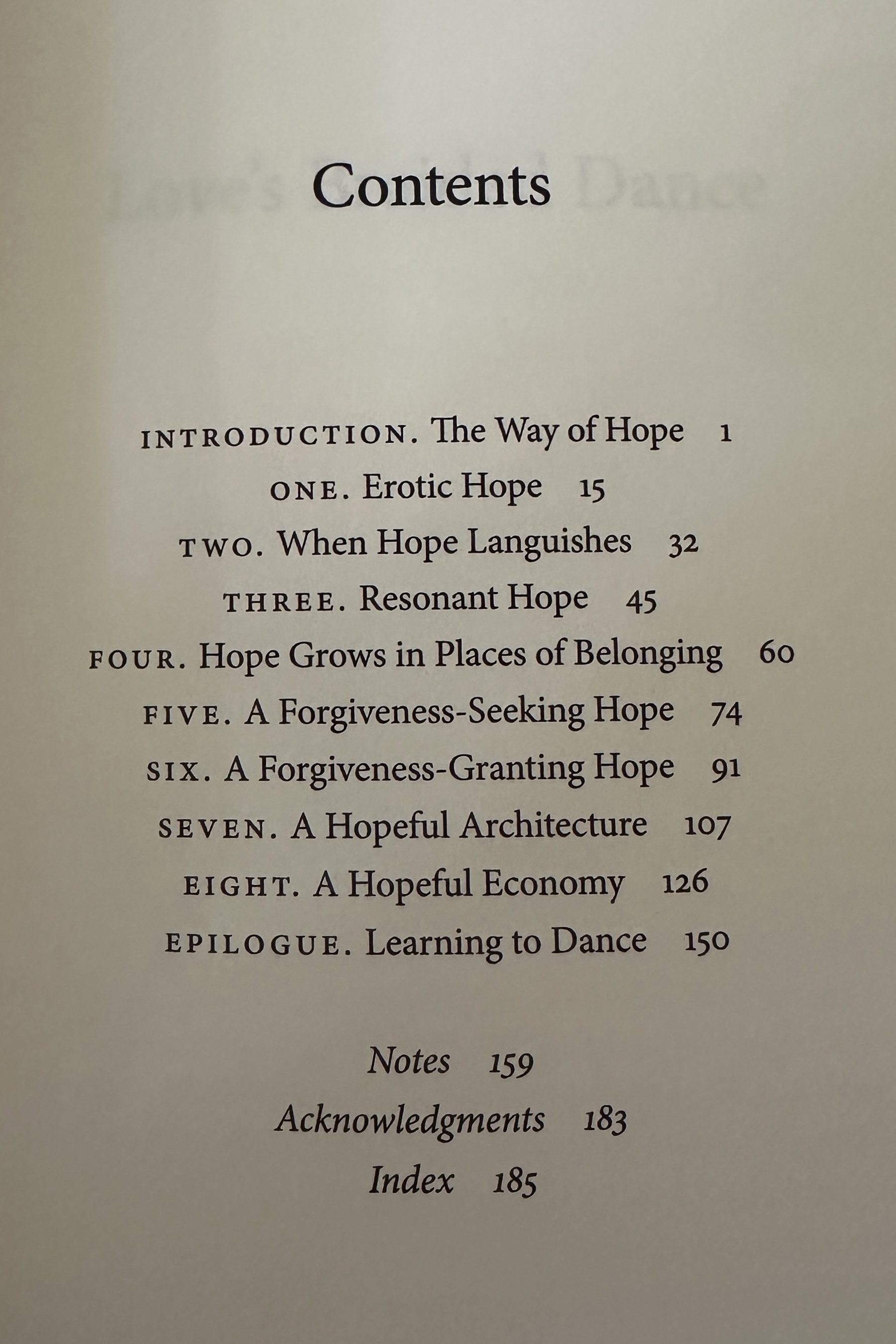

Currently Reading: Love’s Braided Dance: Hope in a Time of Crisis by Norman Wirzba 📚

A logic governs the way of hope. It is difficult to articulate because the way of hope is not linear, systematic, or smooth. It does not follow twelve neatly defined steps that, when taken in succession, lead a person into a hopeful manner of being. Instead, it is often meandering and circuitous as people attempt to live faithfully and mercifully with each other. False starts, improper motivations, and harmful choices, but also felicitous decisions, serendipitous encounters, and enduring commitments, often reveal themselves only along the way. This is why this book’s chapters take the form of essays that explore paths into what I take to be hopes animating logic. My aim is to narrate the experiences and journeys of various people so that the heart of a hopeful way of being can come into view.

These chapters, then, are complementary sketches that together draw a picture of what a hopeful life looks like, or, more exactly, they offer a series of improvisational movements that make a compelling theatrical performance in which hope appears. As people go through life, what do they encounter, what should they accept, how should they respond, and to what end? Hope registers as the desire to celebrate and further the loveliness and love-worthiness of this life. When we live a hopeful life, love animates what we do and why we do it.

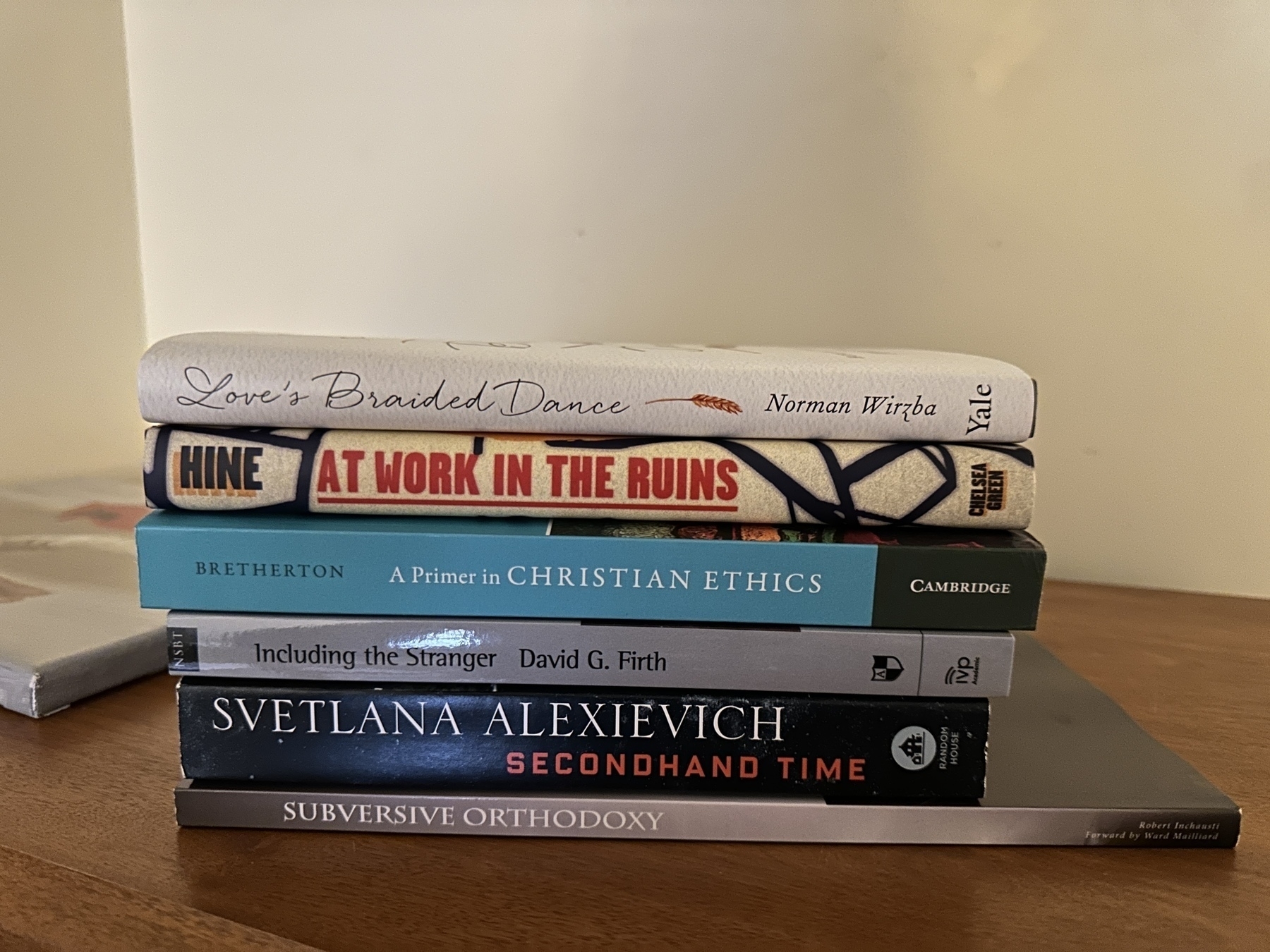

An excellent book haul this week 📚

When I see animals successfully cross the road, I cheer them on. Literally.

While Tolkien certainly had a category for complex moral problems and possessed a deep understanding of the need for wisdom in approaching moral difficulties, he had no category whatever for engaging in evil to secure good ends. One’s moment in history did not let one off the hook of acting with honour.

Man, Jack Meader’s essay on Tolkien’s “long defeat” was the perfect closing to the fall issue of Comment. Some essays carry the weight of a book that you want to have proudly displayed on the shelf so you can reference them for years to come. Another reason why it’s worth subscribing in print!

I love this take on Tolkien’s Shire:

In a letter written later in life, Tolkien remarked that “by 1918 all but one of my close friends were dead.” In 1918 Tolkien was only twenty-six years old. World War I not only robbed Tolkien of his friends; it also deprived virtually all its European combatants of unfathomably large numbers of young men—permanently changing Europe’s demographics, culture, and ways of life. The world Tolkien had known as a young man really was conclusively overthrown and destroyed by the Great War. *Indeed, it is not altogether wrong to regard his creation of the Shire and even the fellowship of wandering men as a kind of love letter to that lost world, an attempt to show others who would never know it themselves what had once been.

What if we all challenged ourselves to write such a love letter — to act as though we were writing a love letter to the world?