Nice day to spread your wings • Did I say this weekend? They say sooner!

Catchin’ up with the Tweet Tweets

Mama House Finch, who never misses anything

And spooks easily

But she and Dada House Finch (red-orange) usually stay close by

Baby Tweet Tweets are almost 2 weeks old, which means they’ll likely be out of the nest this weekend

Will has been especially fascinated with their eyes

On the holiness of unwhole hope — a few lines of poetry, a highly recommended short film, and a thought near the close of Holy Saturday

Got pulled over Friday night for the first time in years. Nine years if memory serves, which is a pretty good stretch considering that in the years preceding that I estimate being pulled over between 30 and 50 times. (Don’t ever let people tell you you can’t change 🙂)

Last week’s warning (phew) could have been avoided if I had

-

put my front license plate on (don’t like it because it makes the collision sensors wonky)

-

consented to have the vehicle pass an inspection (disagreed with the service department about some very mild uneven tread wear and the necessity v. wastefulness of replacing tires which have plenty of good tread left on them)

-

bothered to get the car reregistered … last October (oops)

I’m not a rebel, I’m just stubborn.

Which reminds me…

I’m currently reading: A Living Spirit of Revolt: The Infrapolitics of Anarchism by Žiga Vodovnik 📚

It’s funny how memory works. Just casually hearing the phrase “slave to the system” yesterday suddenly had me singing the lyrics to a song from my high school years that I haven’t heard in 20 years:

Lifestyle and obsession

Diamond rings get you nothin' but a lifelong lesson

And your pocket book stressin'

You’re a slave to the system, workin' jobs that you hate

For that shit you don’t need

It’s too bad the world is based on greed

That album came out in 2000 and it’s shocking how many lyrics I can still remember from it.

I was also surprised by two things yesterday:

-

I had no idea Jacoby Shaddix is a Christian

-

And I would never have imagined him doing a duet with Carrie Underwood

These are simple, idiosyncratic, anarchic revelations, but it’s important to let life surprise you.

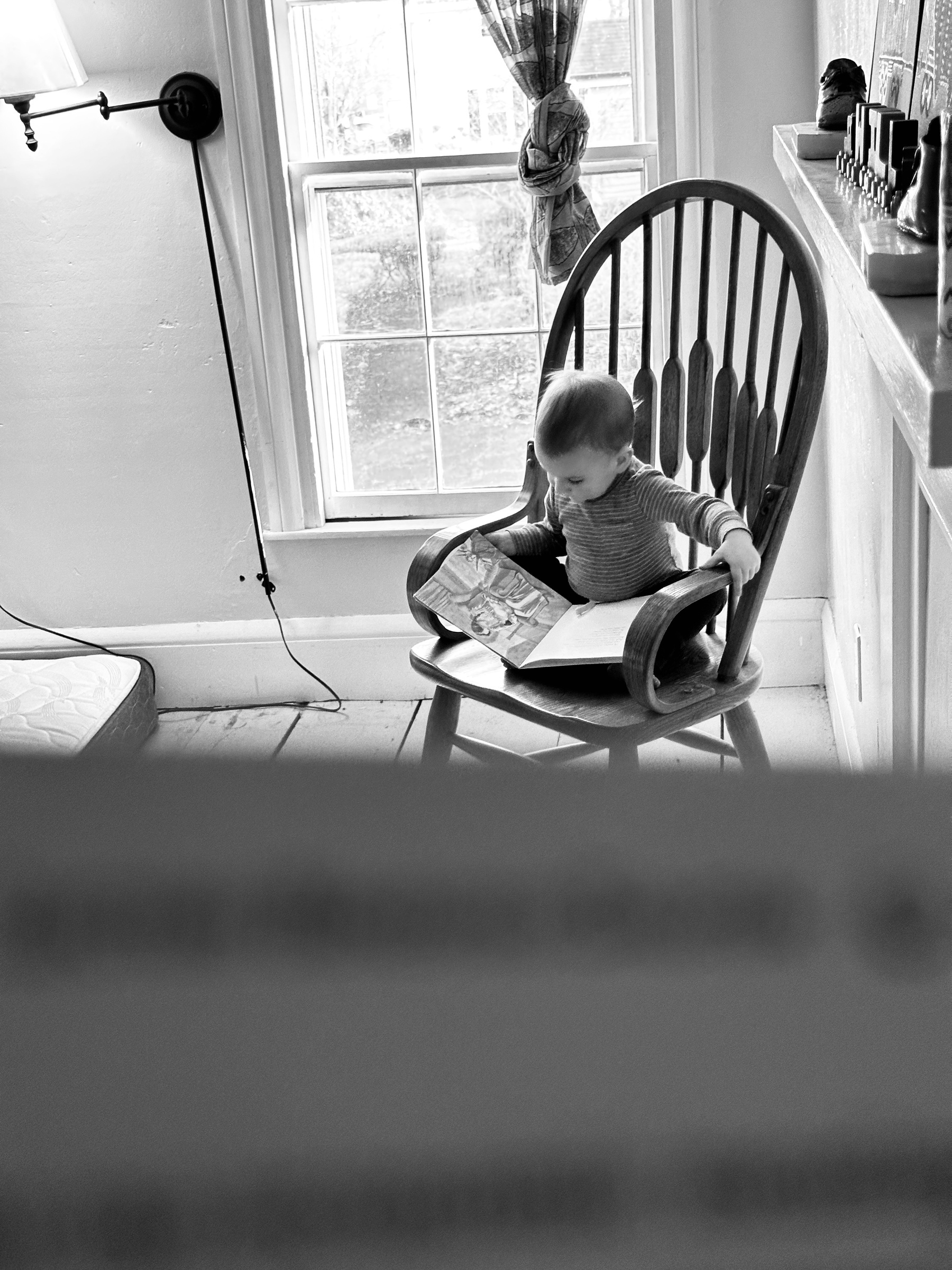

Curiosity • Springtime means birds, and for a 15-month-old it also means moving from human what-does-a-birdie-say “tweet tweets” to the real ones, the sound of which catches Will’s ear throughout the day, stops him in his tracks and redirects him to the nearest window. The other day he noticed some tweet tweets coming from the front light fixture. And yesterday, he heard some brand new baby tweet tweets coming from the nest. I think he wants to be friends 🙂