Kitchen Chalk Talk

Kitchen Chalk Talk

This all happens within a schizophrenic culture that simultaneously celebrates every product and innovation that makes something easier and lower-effort, while also celebrating effort and self-discipline — and, at the same time, ignoring millennia of wisdom on how ascetic practice actually works and pretending it’s just a matter of individual choice and volition:

Now, as the tide of internet slop rises around us, it should already be clear that this industrialisation of thought is making us as cognitively sedentary, as cars and labour-saving machines made us physically so. Accordingly, cognitive fitness is on track to become as much an ascetic practice as staying fit in culture of couch potatoes. Now, if we’re going to talk about cultivating the kind of physical and cognitive askesis required to avoid becoming physically and mentally flabby in this context, that means reckoning with the noonday demon. And that means reckoning with technology of acedia that is to cognitive askesis as smoking is to the physical kind: our phones.[…]

Perhaps there’s scope for careful engagement. But it should be clear that there are also whole industries out there today, whose sole aim is getting rich by feeding and legitimising your noonday demon, and making it difficult for you to sustain the self-discipline needed to flourish. And sure, there is a certain amount we can do as individuals to resist: the cheery self-help post. But I think this is a collective action problem, too, which is to say a moral one. We should take the whispering noonday demon — and those who profit from it — a great deal more seriously than we do.

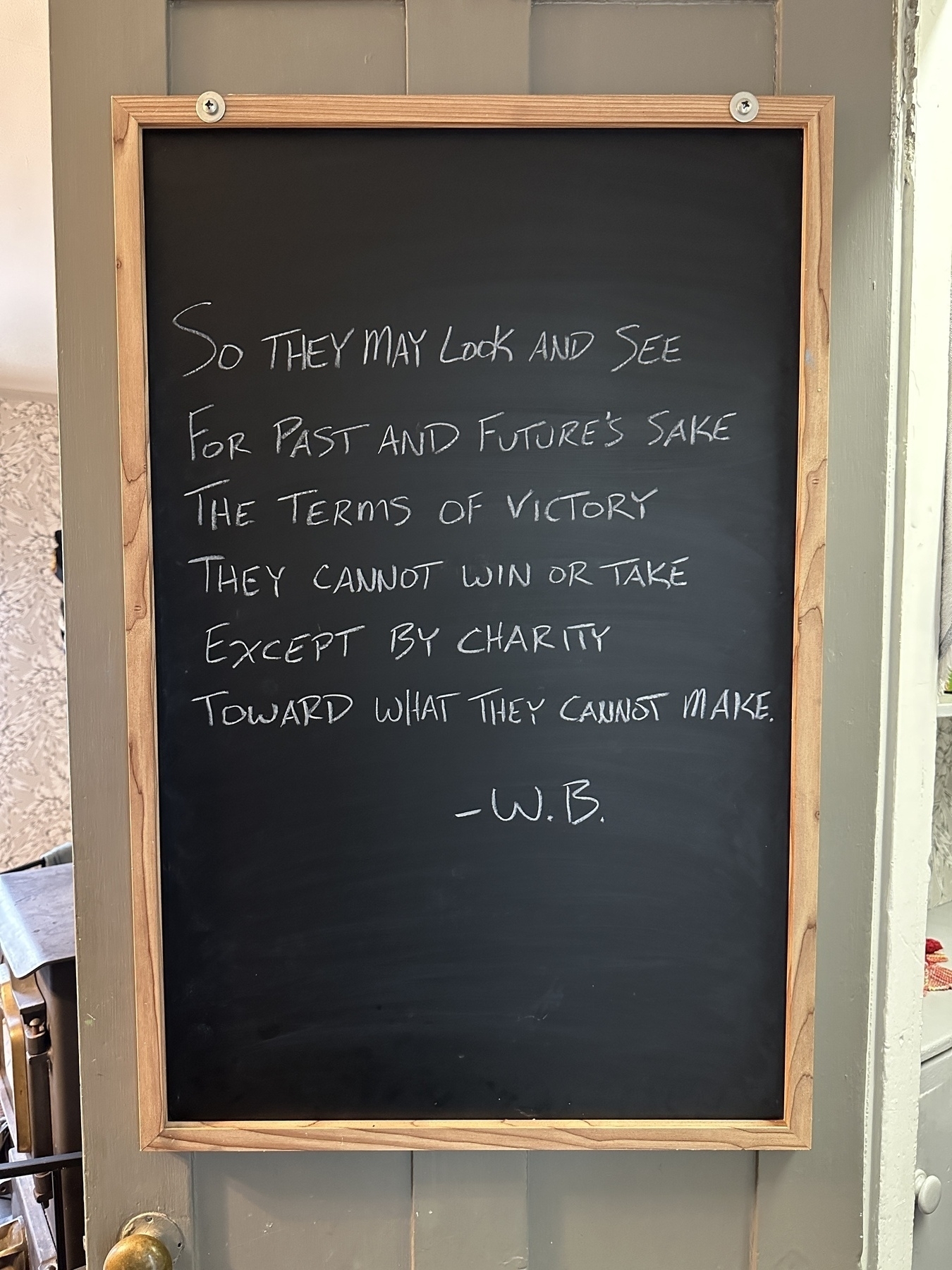

Lasch via Miller via Hummel:

These people have sold the rest of us on their way of life, but it is their way of life, first and foremost, and it reflects their values, their rootless existence, their craving for novelty and contempt for the past, their confusion of reality with electronically mediated images of reality.

Daniel Hummel’s essay on the humanism of Jimmy Carter and Christopher Lasch is an excellent and important one.

It’s not the first time Sudan’s had a genocide. It’s not the first time Sudan’s had a famine. It’s not the first time Sudan’s had a civil war in the last 10 years, 20 years, 30 years,” he said. “As bad as it is—and it’s never been this bad in Sudan’s history—it feels like history is repeating itself.

Honestly, I know it’s not a straightforward story, but the fact that The Dispatch can do write-ups like this on Sudan and not even mention the history of Chevron oil or U.S. and Russian involvement is deeply saddening.

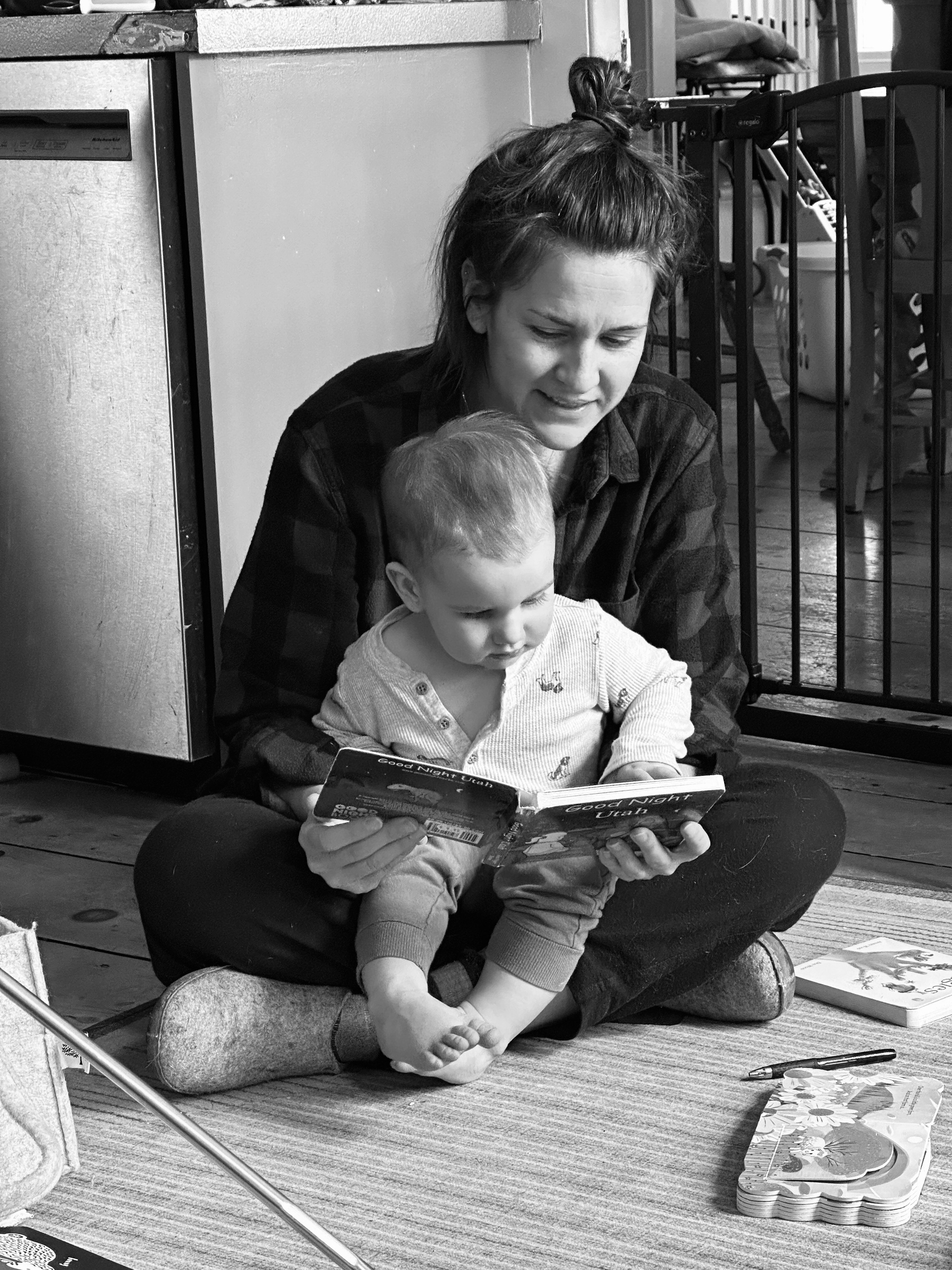

Someday he’s gonna owe this mama a lanyard.

For the discerning intellect of Man,

When wedded to this goodly universe

In love and holy passion, shall find these

A simple produce of the common day.

—Wordsworth

Charles Taylor can introduce digressions whenever he wants.

“Tell the stories. Follow the principles. Do the work.… Don’t go gated.”

Finished reading: Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City by Matthew Desmond 📚

One city must build; another must destroy. If our cities and towns are rich in diversity—with unique textures and styles, gifts and problems—so too must be our solutions.

Whatever our way out of this mess, one thing is certain. This degree of inequality, this withdrawal of opportunity, this cold denial of basic needs, this endorsement of pointless suffering—by no American value is this situation justified. No moral code or ethical principle, no piece of scripture or holy teaching, can be summoned to defend what we have allowed our country to become.