Finished reading: The Home Place by Wright Morris 📚

I put a roof nail in it here.

Finished reading: The Home Place by Wright Morris 📚

I put a roof nail in it here.

I plan to be very mostly offline this summer. Work will be shifting back closer to home and I would like to be there — as mentally there as physically.

I think I have been in cognitive retreat (or worse) for a while now, and I’m feeling more and more stuck inside the fog machine that is my brain. I have any of a dozen half-finished projects around the house that I haven’t even tried to find time for. I have emails and letters that have gone unanswered embarrassingly, shamefully too long — and I really do mean shamefully. I can probably paint a pretty sympathetic picture about age, parenthood, travel and 12-hr shifts — and, of course, the economy. But I also know that the sympathetic picture would not be the whole picture.

Honestly, this post is itself part of the problem. I jotted the gist down on my iPhone while I was making coffee last week, and I’ve since spent many of those spare, reflexively-pull-out-the-phone moments adding to it. (I’m doing it right now instead of talking to my coworkers.)

Here’s something I’m having to admit to myself: the question What can I post online? is occupying far too much headspace.

I’ve tended to treat micro.blog as something entirely other than social media, and that for a couple reasons that I’ve mentioned before. One is that micro.blog does such an excellent job avoiding all the known nefarious pitfalls of basically every major social media platform.

But the main reason is that I started using it explicitly as a blog for those who are not on micro.blog. It started as 100% for the “Why aren’t you on Facebook?” friends and family. (In fact, most people who I know in real life don’t even know that it’s technically… dun dun dunnnnn… social media.) I still mostly post on it with those folks in mind, but the percentage has dropped. And while I really don’t know what number to give it, I do know that I have mixed feelings about Why I Post Online.

I explained some of what’s driving this a couple years ago in “Looking for the Cracks,” the title of which I don’t think I did enough to emphasize. But more importantly, the substance of which I have not done enough to live.

Anyway, summer feels like a damn good time to shift focus back to earth, to make looking out my window and walking out my door — and making coffee — enjoyable unto themselves. Hopefully I’ll say more in a newsletter soon.

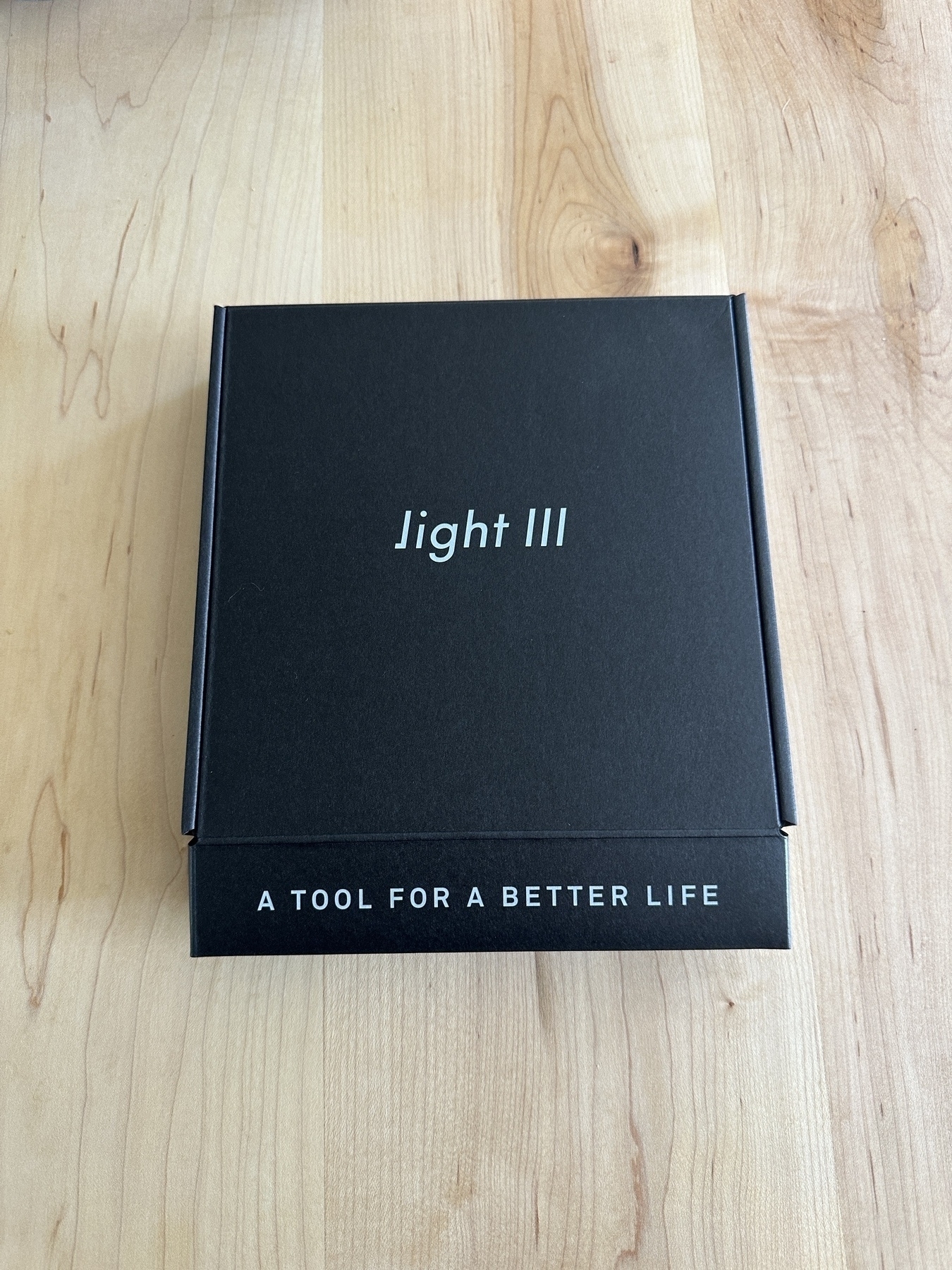

The moment has arrived. Happy New Phone in the Mail Day!

No matter where you’ve wandered off to

Or how far afield you’ve strayed

Underneath a heavy ocean

Deep inside a rotten cave

Still you sing a song that’s holy

Still you burn a perfect flame

What is lost won’t be forgotten

What is good will never change

“Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.” — and 7 more faces of AI impact.

Three separate, cross-pressured but overlapping points to put a pin in (listed in, I think, increasing neglect and significance):

As Morten Høi Jensen emphasizes in the piece above, it was happening, in broad daylight, despite the fact that very bright and attentive people thought it “couldn’t or wouldn’t happen here.”

It didn’t have to happen. This doesn’t seem to be Jensen’s point, or at least not the one he stresses, but it’s in the piece. It was not inevitable. (Meacham’s Lincoln is excellent on this point, something I tried to say here, and that I need reminding of.)

Not everything can or should be reduced to its place in a chain of events. Maybe you have the power to change something, maybe you don’t. But life can be lived well and joyfully regardless of what happens next. This is the here-and-now of what Buechner called the untouchable “having-beenness” of time. As Thomas Mann himself put it:

Even stories with a sorry ending have their moments of glory, great and small, and it is proper to view these moments, not in the light of their ending, but in their own light: their reality is no less powerful than the reality of their ending.

Eve Tushnet makes me want to read William Dalrymple’s From the Holy Mountain.

And she also makes me want to subscribe to Conor McDonough’s The White Stone.

How many deaths of other people’s children by bombing or starvation are we willing to accept in order that we may be free, affluent, and (supposedly) at peace?