Whenever I post something online, or, frankly, use the internet at all:

Whenever I post something online, or, frankly, use the internet at all:

Grant Wacker’s 4 major contexts and 11 minor contexts of (God and religion in) the American story reminds me of something from Martin Luther:

If I profess with the loudest voice and clearest exposition every portion of the truth of God except precisely that little point which the world and the devil are at that moment attacking, I am not confessing Christ, however boldly I may be professing him. Where the battle rages, there the loyalty of the soldier is proved, and to be steady on all the battlefield besides is mere flight and disgrace if he flinches at that point.

It’s not about killing drug traffickers; it’s not even about signaling to drug traffickers or about drug trafficking at all — “it’s about training the military to do bad things”, to do them without question, and about training everyone, from the CJCS on down to Joe Plumber, to sanction or tolerate it.

And this week’s bumper sticker award goes to the little blue, 30-year-old Tacoma out in front of Fernald’s: Slower Than Fast

Nate Hagens on those three beautiful, underused, underappreciated words: I don’t know:

This is a repeating pattern in our culture: certainty beats caution — and the costs come later. “And the costs come later” might currently be a good mnemonic tagline for homo sapiens sapiens.

Bath, ME • 17th Annual Trick or Treat TROMP

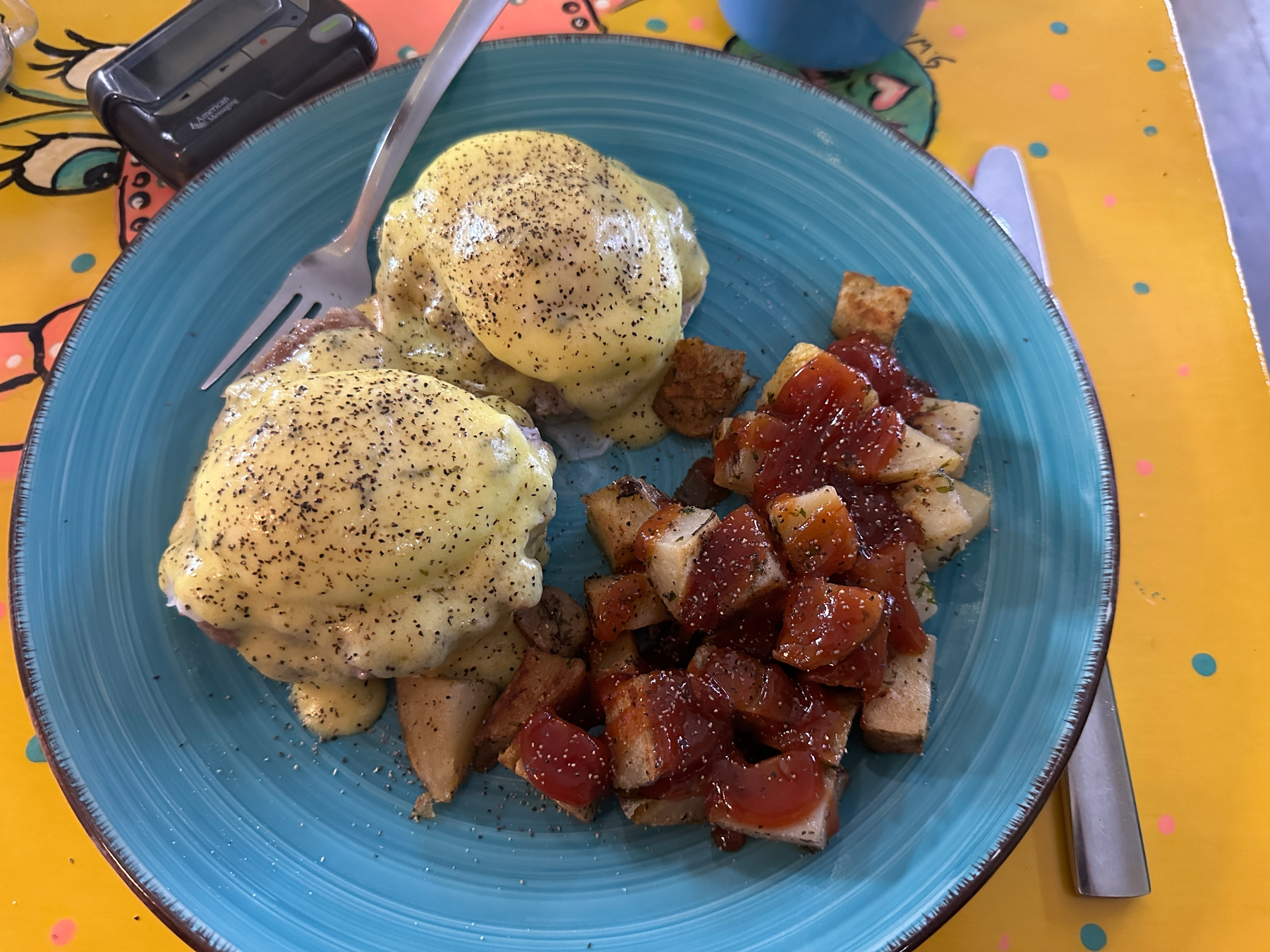

Diners that open before the sun rises; canary-yellow table tops; pepper flakes falling over house-made hollandaise sauce…

Further, the author argues that we’re actually in imminent danger of ceasing to be political animals at all. Politics being the art of asking “how should we live together?”, there’s little reason to wonder about such questions if we rarely or never, well, live together. Barba-Kay argues that we tend to resolve our cognitive dissonance by outsourcing all the choices that do matter and consoling ourselves with a plethora of choices that don’t. So we have no choice when it comes to closing local businesses, but that’s all right, you can still “decide” what to stream on TV or which people you want to yell at on the internet, since those sorts of choices are free in inverse proportion to their significance.

From the wonderful Anna Havron:

…perhaps I had to care about it much more in the past, in order to be freed to care less about it now.

Sometimes when I remember to rely on this source of wiser intelligence - to call on it for help, and to listen for its responses - it feels like I’m traveling in an intentional river current that is carrying me to exactly where I need to be, to exactly the people and resources I need, to deal with what I, on my own, have been caring too much or too little about.